Mais vida

Estudos experimentais realizados por cientistas da Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp) mostram fortes efeitos dos flavonoides no combate ao câncer.

Flavonoides são compostos químicos encontrados em diversos vegetais, tendo-se destacado nos anos recentes estudos com flavonoides extraídos das uvas (presente no vinho) e nas cebolas.

Camila de Andrade Camargo e Hiroshi Aoyama testaram os flavonoides quercetina, narigina e morina, além do acetoxi DMU, que se mostraram promissores na regressão do câncer e no aumento da sobrevida, em experimentos com animais.

Embora os resultados sejam ainda preliminares, o tratamento terapêutico com todos os quatro compostos foi capaz de inibir em até 50% o crescimento tumoral do carcinossarcoma de Walker 256, com um aumento médio na sobrevida de 60% dos animais na vigência de tratamento.

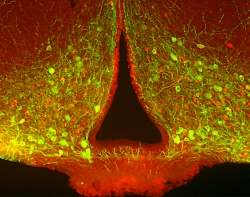

Caquexia

Outro avanço comemorado pelos pesquisadores foi a diminuição da caquexia provocada pelo câncer em estágios avançados, além de resultados enzimáticos substantivos.

A síndrome da caquexia representa um estado metabólico complexo no organismo do paciente.

Ela é geralmente caracterizada pela perda de peso progressiva, que ocorre devido ao uso das reservas de gorduras e também dos músculos do corpo do paciente para o suprimento do tumor.

Portanto, esta síndrome está diretamente ligada à baixa qualidade de vida, sendo responsável por uma diminuição significativa no tempo de vida dos pacientes com câncer. No trabalho de Camila e de Hiroshi Aoyama, foi possível abrandar essa caquexia.

Resveratrol

O antioxidante mais conhecido é o resveratrol, presente no vinho e muito estudado por causa do chamado "paradoxo francês", uma expressão adotada pelos nutricionistas para se referir ao notório paradoxo entre a alimentação dos franceses e a sua saúde que, dentre os seus hábitos mais comuns, está a ingestão de um cálice de vinho por dia.

"Alguns estudos relacionados ao consumo de vinho deixaram claro que as pessoas que o consomem moderadamente podem ter menos doenças cardíacas que as pessoas que não o ingerem", assegura Camila de Andrade.

Alguns estudos, menciona Hiroshi Aoyama, apontam que o consumo de alimentos ricos nesses compostos está associado a uma redução no risco de desenvolvimento de certas doenças, provavelmente por sua ação antioxidante, que protege as células contra os danos causados pelos ataques dos radicais livres.

O principal mecanismo protetor se dá através da diminuição na oxidação das moléculas de LDL (o "colesterol ruim") e do aumento do HDL (o "bom colesterol"), melhorando o perfil de gorduras que circulam no sangue.

Além disso, eles demonstram ação anti-inflamatória, o que reduziria os riscos cardiovasculares. Muitos deles foram descritos também como potentes anti-hemorrágicos, antialérgicos e anti-hipertensivos, dentre outras atividades.

Sem excessos

Hiroshi adverte que os flavonoides, não obstante a sua ação antioxidante, dependendo de sua concentração, podem atuar também como pró-oxidantes, levando ao aparecimento de radicais livres, espécies reativas de oxigênio que podem causar danos ao organismo.

No caso do experimento agora realizado, uma certa dose de cada composto mostrou-se benéfica. Mas, aumentando-a, o animal não apresentou melhora nenhuma.

"Por isso deve-se ter cuidado para que as pessoas não se adiantem querendo aplicar os nossos conhecimentos, ainda básicos. Ao invés de terem um efeito benéfico, poderão ter prejuízos se os utilizarem em grandes quantidades," afirmou o pesquisador.