ScienceDaily (July 21, 2011) — The loss of a protein that coats sperm may explain a significant proportion of infertility in men worldwide, according to a study by an international team of researchers led by UC Davis. The research could open up new ways to screen and treat couples for infertility.

|

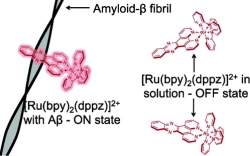

Top: These are normal human sperm. Green dots show the presence of a sugary molecule that allows the sperm to swim through cervical mucus. Bottom: These are sperm from a donor with a defective gene for the coating protein. These sperm look normal and can swim, but have difficulty penetrating mucus. |

A paper describing the work is published July 20 in the journalScience Translational Medicine.

The protein DEFB126 acts as a "cloaking device," allowing sperm to swim through mucus and avoid the immune system in order to reach the egg, said Gary Cherr, a professor at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory and Center for Health and Environment. Cherr is the senior author of the paper.

But the UC Davis researchers found that many men carry a defective gene for DEFB126. A survey of samples from the U.S., United Kingdom and China showed that as many as a quarter of men worldwide carry two copies of the defective gene -- which may significantly affect their fertility.

Infertility affects 10 to 15 percent of the U.S. population, said John Gould, associate professor of urology at UC Davis, who was not involved in the research. About half of those cases involve problems with male fertility.

One of the mysteries of human fertility is that sperm quality and quantity seem to have little do with whether or not a man is fertile, said Ted Tollner, first author of the paper, who carried out the work as a postdoctoral scholar with Cherr. Tollner is now an adjunct assistant professor in the UC Davis Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

"In 70 percent of men, you can't explain their infertility on the basis of sperm count and quality," Cherr said. Studies like this may give us opportunities to explain these cases, Gould said.

If the discovery were successfully developed into a test, it could be used to send couples directly to treatment with intracytoplasmic sperm injection or ICSI, in which eggs are removed from the woman and injected directly with sperm, avoiding an expensive workup to exclude other causes, Gould said.

Tollner and Cherr were looking for ways to make contraceptive vaccines when they started looking at DEFB126. The protein belongs to a class of molecules called defensins, natural germ-killers found on mucosal surfaces. DEFB126 is produced in the epididymis, the structure where sperm are stored after they are produced in the testes, and deposited onto sperm in the epididymis to form a thick coat.

Tollner and Cherr were trying to make antibodies to the human protein, without much success. So they enlisted the help of Professor Charles Bevins, an expert on defensins who had just joined the UC Davis Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology.

Bevins' lab made a recombinant copy of the human DEFB126 gene, with the aim of generating a purified protein that Tollner and Cherr could use to create antibodies. On their first attempt, they found the gene had a mutation that prevented it from making a protein. But when they used sperm from a different donor, they were able to make the normal protein.

"If we hadn't seen this in the first clone, we would be confused to this day," Bevins said.

Sperm from men with the defective DEFB126 genes look normal under a microscope and swim around like normal sperm. But they are far less able to swim through an artificial gel made to resemble human cervical mucus.

When the normal protein is added to the sperm, they recover their normal abilities, the team found.

Working with Edward Hollox at the University of Leicester, England, Xiping Xu at the University of Illinois, Chicago, and Scott Venners at Simon Fraser University, Canada, the researchers were able to look at the frequency of the gene in DNA samples from people in the U.S., United Kingdom, China, Japan and Africa.

They found that worldwide, about half of all men carry one defective copy; a quarter have two defective copies and therefore make sperm that are poor at swimming through mucus.

In collaboration with Xue Liu and other scientists at Anhui Medical University in Anhui, China, the epidemiology team headed by Venners was able to look at the effect of the mutation on a group of couples trying to conceive. They found a statistically significant decrease in the number of pregnancies in couples where the man carried two copies of the defective DEFB126 gene.

Why should a mutation that affects fertility be so astonishingly common? It may be that heterozygotes -- men with one normal and one defective gene, but normal fertility -- are advantaged in some way, Tollner said.

Tollner noted that compared to sperm from monkeys and other mammals, human sperm are typically poor quality, slow-swimming, and with a high rate of defective cells. It's possible that because humans, unlike most mammals, breed in long-term monogamous relationships, sperm quality just does not matter very much, Cherr said.

However, some researchers believe that, for reasons unknown, human male fertility has been falling worldwide in recent decades. That decline might be unmasking the problems associated with the defective DEFB126 gene.

Cherr said that they hope next to work with a major infertility program in the U.S. to further explore the role of the mutation.

Other authors of the paper are: Ashley Yudin and James Overstreet, Center for Health and Environment, and Robert Kays, Tsang Lau, Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, UC Davis; and Genfu Tang and Houxun Xing, Anhui Medical University.

The study was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.