A cada ano, milhares de brasileiros morrem de câncer. Em 2008, por exemplo, foram mais de 167 mil óbitos, segundo dados do Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde (Datasus). Os diversos pontos que envolvem a dinâmica dessa doença e suas terapias são assuntos de estudos em todo o mundo. No Instituto Nacional do Câncer (Inca), Adriana Cesar Bonomo, Cientista do Nosso Estado da FAPERJ, desenvolve duas linhas de pesquisa: uma sobre os mecanismos da doença do enxerto contra hospedeiro (DECH), que acomete cerca de 70% dos pacientes no pós-transplante de medula óssea e seus possíveis mecanismos de regulação; e outra que estuda a interação do sistema imune e a metástase intraóssea.

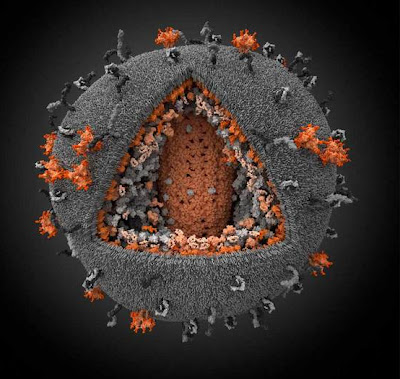

Adriana esclarece que transplante de medula óssea é um tratamento proposto para certas doenças que afetam células sanguíneas, como leucemias e linfomas. O procedimento, resumidamente, consiste em substituir a medula óssea doente, ou deficitária, por células retiradas de uma medula óssea saudável. “O paciente recebe o transplante como se fosse uma transfusão de sangue. Ao cair na corrente sanguínea, as células imaturas se alojam na região da medula e se diferenciam em células sadias, o que chamamos de ‘pega’”, conta.

De acordo com a pesquisadora, o transplante pode ser autogênico, quando proveniente do próprio paciente, ou alogênico, quando proveniente de doador. “Neste último é que ocorre a doença do enxerto”, conta Adriana. Ela explica que no material transplantado há células imaturas e células já diferenciadas, que produzem efeito antitumoral. Entre estas últimas, estão os linfócitos que também geram uma resposta anti-hospedeiro, ou seja, uma rejeição celular. “Essa doença é como se fosse uma doença autoimune, quando o sistema imunológico ataca o próprio organismo”, exemplifica.

Em sua pesquisa, mais do que estudar a dinâmica da doença do enxerto, Adriana busca meios de modular o transplante, o que significa controlar a resposta anti-hospedeiro sem atrapalhar o efeito antitumoral. Uma solução pareceria óbvia: retirar os linfócitos do material a ser transplantado para evitar a rejeição. A pesquisadora adverte, contudo, que, ao se fazer isso, o índice de o tumor reaparecer é de 60% e as chances de ocorrer a “pega” das células transplantadas também diminui.

A pesquisadora conta que uma forma de modulação, descrita na literatura, se resume em transplantar o conteúdo recolhido do sangue periférico de um doador tratado com fator de crescimento para células sanguíneas, o que faz aumentar o número de células-tronco circulante no sangue. O resultado apresentado foi a diminuição na incidência da doença do enxerto, apesar do material conter dez vezes mais linfócitos. A explicação seria de que a droga teria efeito modulador.

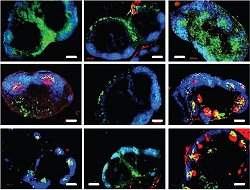

Ao observar o elevado número de granulócitos – tipo de células de defesa – no material transplantado, contudo, o grupo de pesquisa de Adriana atentou para outra hipótese. Viram, in vitro, que granulócitos suprem a atividade dos linfócitos. Segundo a pesquisadora, ao transpor a metodologia para camundongos transplantados tratados que também receberam granulócitos houve 100% de inibição da doença do enxerto, confirmando in vivo os resultados obtidos in vitro com células humanas.

Na etapa atual, Adriana estuda a ação dessas células para entender como agem na prevenção da doença. Outra dúvida que surge é se o efeito antitumoral é preservado. “Antes de propor um modelo experimental em humanos precisamos aprofundar esses conhecimentos. Cabe destacar que os estudos com granulócitos são realizados em parceria com a professora Tereza Christina Barja-Fidalgo, da Uerj”, diz.

|

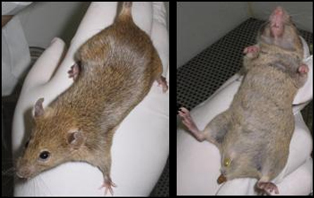

Nos testes de indução de tolerância oral, com camundongos, evitou-se a doença do enxerto em 100% dos casos. |

Outra possibilidade de modulação, pesquisada por Adriana, é por meio da indução de tolerância oral: o camundongo doador recebe proteínas do camundongo receptor, acrescida de probióticos – organismos vivos bacterianos, neste caso lactoccocos –, que conferem benefícios à saúde do hospedeiro. O objetivo é que, no pós-transplante, não haja resposta imunológica agressora autoimune.

“Após a indução dessa tolerância oral, a medula do animal doador foi transplantada em outro animal e obtivemos 100% de inibição da doença do enxerto. Agora, implantamos um tumor no animal a ser transplantado e vamos repetir o experimento, para ver se a resposta antitumoral é preservada. Esses estudos são realizados em parceria com a professora Ana Maria de Faria, da UFMG”, explica a pesquisadora.

Outra linha de pesquisa

De acordo com Adriana, a segunda linha de pesquisa consiste em compreender a relação dos linfócitos T e a dinâmica do ciclo vicioso da metástase intraóssea. “O ciclo vicioso é quando células com potencial Segundo metastásico se desprendem do tumor primário e chegam à medula. Lá se desenvolvem, favorecendo o crescimento de células que produzem osso, que por sua vez favorecem a produção de células que ‘comem’ osso. Elas liberam fatores de crescimento que mantêm o desenvolvimento do tumor”, esclarece.

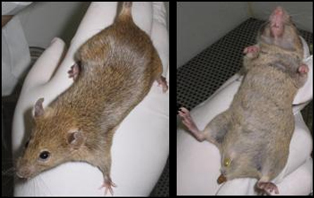

Ela explica como foi o experimento: “células-mãe de tumor de mama e células subclonadas das células-mãe foram implantadas em mamas de camundongos fêmeas. O primeiro tipo faz metástase e o segundo produz apenas tumor local”, conta a pesquisadora, ressaltando que o modelo de tumor de mama foi escolhido porque 70% dos casos evoluem para metástase intraóssea.

Segundo Adriana, observou-se que quando o tumor primário tem potencial metastásico, os linfócitos T atuam de modo a favorecer a implantação da metástase intraóssea. “Antes das células metastásicas chegarem ao osso, os linfócitos T preparam o nicho pré-metastásico, local propício para o crescimento do tumor”, relata.

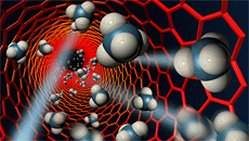

Para Adriana, a solução seria implantar um fator antitumor que se agregasse aos linfócitos T, com o objetivo de silenciar a expressão das moléculas que favorecem o crescimento das lesões ósseas. “Acreditamos que duas citocinas estejam diretamente envolvidas no crescimento das metástases intraósseas. Pretendemos inibir, experimentalmente, a expressão dessas duas citocinas nos linfócitos ”, adianta.

Segundo Adriana, os resultados sugerem ainda que a presença de linfócitos que produzem as tais citocinas sirva para estabelecer o prognóstico de pacientes com tumor de mama. “A hipótese é que o tipo de citocina produzida pelos linfócitos das pacientes com tumor de mama indica se o tumor será metastático ou não. Os estudos começarão em breve e contarão com a colaboração do professor Ricardo Bentes Azevedo, da UNB”, aposta.

“Eu coordeno essas linhas de pesquisa, mas a boa execução dos experimentos se deve ao meu grupo, com destaque para a doutoranda Ana Carolina Mercadante, as estudantes Ana Carolina Monteiro e Suelen Perobelli e a técnica Ana Paula Gregório Alves”, destaca. “É importante que, cada vez mais, se realizem pesquisas para aumentar a base do conhecimento sobre a dinâmica dos tumores e suas terapias”, conclui Adriana. O trabalho realizado pelo Inca, portanto, reforça o apelo da pesquisadora. Por um lado, o instituto abriga várias linhas de pesquisas de base. Por outro, atua direto com a população, oferecendo tratamentos oncológicos e desenvolvendo campanhas de prevenção.