Saúde dos brasileiros é tema de edição especial da revista The Lancet Lançamento da série composta por seis artigos contará com a presença do ministro da Saúde, Alexandre Padilha  A ABRASCO estará participando do lançamento de uma série de seis artigos intitulada “A Saúde dos Brasileiros” da revista inglesa The Lancet, representada por seu presidente, Luiz Augusto Facchini, e pela vice-presidente, Lígia Bahia, coautora de um dos artigos. A revista é uma das publicações médicas mais influentes do mundo e a edição especial, coordenada pelo abrasquiano Cesar Victora, pesquisador da UFPel e presidente eleito da Associação Internacional de Epidemiologia, é uma ampla revisão sobre os determinantes e as condições de saúde da população brasileira. O evento é aberto ao público e não haverá inscrição. A solenidade será realizada na sede da Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde (Opas), em Brasília, no dia 9, às 14h, e contará com a presença do Ministro da Saúde, Alexandre Padilha. A ABRASCO estará participando do lançamento de uma série de seis artigos intitulada “A Saúde dos Brasileiros” da revista inglesa The Lancet, representada por seu presidente, Luiz Augusto Facchini, e pela vice-presidente, Lígia Bahia, coautora de um dos artigos. A revista é uma das publicações médicas mais influentes do mundo e a edição especial, coordenada pelo abrasquiano Cesar Victora, pesquisador da UFPel e presidente eleito da Associação Internacional de Epidemiologia, é uma ampla revisão sobre os determinantes e as condições de saúde da população brasileira. O evento é aberto ao público e não haverá inscrição. A solenidade será realizada na sede da Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde (Opas), em Brasília, no dia 9, às 14h, e contará com a presença do Ministro da Saúde, Alexandre Padilha.Baseados em uma extensa revisão de documentos existentes, e em análises originais de dados epidemiológicos, uma equipe de 29 especialistas em saúde pública preparou seis artigos científicos que descrevem a história da assistência à saúde no Brasil, com ênfase na implantação do Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS), assim como a evolução recente dos principais problemas de saúde que afligem nossa população, bem como dos seus principais determinantes e fatores de risco. Artigos específicos descrevem o desenvolvimento do nosso sistema de saúde, a saúde de mães e crianças; as doenças infecciosas; as doenças crônicas não transmissíveis; e as lesões físicas e violências. Embora importantes problemas de saúde estejam sendo reduzidos, muito ainda precisa ser feito para que todos brasileiros atinjam níveis de saúde compatíveis com aqueles observados em países desenvolvidos. Na busca de atingir tal objetivo, a série de artigos culmina com um chamado para a ação dirigido a todos os setores da nossa sociedade: governo, trabalhadores de saúde, setor privado, universidades e instituições de ensino e pesquisa e a sociedade civil em geral. A série completa com os seis artigos e com comentários redigidos pelos editores da revista e por pesquisadores convidados poderá ser acessada a partir de 9 de maio no site da Revista. |

Neste Blog realizamos: 1 - Atualização sobre SAÚDE PÚBLICA, PESQUISA BIOMÉDICA E BIOSSEGURANÇA. 2 - Atualização sobre a ocorrência de Doenças de importância em animais de laboratório e outras espécies. 3 - Troca de Informações sobre Doenças Infecciosas, Zoonoses, Licenciamento Ambiental, Defesa Sanitária Animal, Vigilância Sanitária, Boas Práticas de Laboratório e demais assuntos relacionados à sanidade e Saúde Pública.

Pesquisar Neste Blog

sábado, 7 de maio de 2011

BOLETIM INFORMATIVO ABRASCO

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

09:12

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Efeitos da nanopartículas sobre a saúde podem estar errados

|

| "Todos os trabalhos anteriores precisam ser reavaliados para explicar os efeitos da sedimentação sobre a dosimetria das nanopartículas", concluem os autores. |

Nanotecnologia perigosa

Um detalhe negligenciado ao se projetar os experimentos científicos pode invalidar experiências que tentam medir o efeito das nanopartículas sobre a saúde humana.

Embora as nanopartículas - partículas com dimensões na faixa dos bilionésimos de metro - estejam cada vez mais sendo utilizadas para levar medicamentos até pontos específicos do corpo, pouco se sabe sobre os efeitos das próprias nanopartículas sobre o organismo.

A maioria dos experimentos usa nanopartículas biocompatíveis ou biodegradáveis.

Porém, alguns estudos demonstraram que as nanopartículas podem danificar o DNA das células. Outros pesquisadores chegam a comparar as nanopartículas ao amianto.

Toxicidade

Os estudos - sejam sobre as potenciais aplicações das nanopartículas, seja sobre sua toxicidade - fundamentam-se na capacidade que os cientistas têm para quantificar a interação entre as nanopartículas e as células, especialmente a absorção (ingestão) de nanopartículas pelas células.

Nos testes-padrão de laboratório, que medem a atividade biológica das nanopartículas, as células são colocadas em um prato de vidro - um disco de Petri - e um meio de cultura contendo nanopartículas é despejado em cima delas.

Isto parecia ser o suficiente até agora, segundo a avaliação dos cientistas.

Mas Younan Xia e seus colegas da Universidade Washington, nos Estados Unidos, começaram a questionar essa simplicidade enquanto faziam experimentos com nanopartículas de ouro - largamente consideradas inofensivas ao corpo humano porque o ouro é muito pouco reativo.

E se as células estivessem de cabeça para baixo? Isso faria alguma diferença? Isso mudaria a taxa de absorção das nanopartículas?

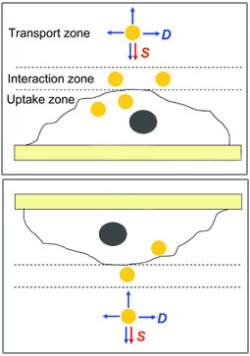

Captação celular de nanopartículas

"As pessoas presumem que, se prepararem uma suspensão, a suspensão teria a mesma concentração em todos os lugares, inclusive na superfície das células," diz Xia.

Uma bateria de experimentos com ambas as configurações - padrão e com as células de cabeça para baixo - mostrou que as nanopartículas acima de determinados tamanhos e pesos vão para o fundo da solução.

Assim, as concentrações de nanopartículas perto da superfície celular são diferentes daquelas medidas na solução como um todo, e a taxa de absorção celular é mais elevada.

Os cientistas então concluem, em um artigo publicado na revista Nature Nanotechnology: "Estudos sobre a captação celular de nanopartículas, que têm sido realizados com células na configuração vertical, podem ter dado origem a dados errôneos e enganosos."

Movimento browninano e gravidade

Os cientistas achavam que poderiam assumir com segurança que a concentração das nanopartículas no fluido próximo às células, que determina a captação celular, era a mesma que a concentração inicial das nanopartículas no meio de cultura.

Isso porque, teoricamente, as partículas são pequenas o suficiente para serem facilmente movidas pelo movimento Browniano, o movimento aleatório das moléculas em um líquido.

Por esse raciocínio, a gravidade não superaria essa força para a difusão, e as nanopartículas ficariam dispersas na solução, em vez de se sedimentarem.

Os experimentos mostraram que, para as partículas menores e mais leves, de fato não há disparidade na absorção entre as células na posição vertical e as configurações de cabeça para baixo.

No caso das partículas maiores e mais pesadas, porém, a sedimentação dominou, e as células em posição normal absorveram mais nanopartículas mais do que as células de cabeça para baixo.

Reavaliação

"Todos os trabalhos anteriores precisam ser reavaliados para explicar os efeitos da sedimentação sobre a dosimetria das nanopartículas", concluem os autores.

"Não é diferente com os medicamentos que precisam ser agitados para suspender um pó em água. Se você não agitar o frasco", explica Xia, "você acaba submetendo a si mesmo a sub ou a superdosagens."

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

09:06

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Receita ideal de suco com 7 frutas protege o coração

Suco ideal

Uma pesquisa francesa indica que uma receita que mistura o suco de sete frutas pode diminuir o risco de ataque cardíaco e derrame.

Os cientistas testaram diferentes "vitaminas" com 13 frutas diferentes e descobriram - em testes de laboratório com porcos - que algumas misturas eram mais efetivas em fazer com que as paredes das artérias relaxassem.

A receita ideal, segundo os pesquisadores, inclui frutas fáceis de se encontrar no Brasil, como maçã, uva, morango e acerola.

Mas encontrar os demais ingredientes - mirtilo, lingonberry (amora-alpina ou arando-vermelho) e chokeberry(conhecida nos Estados Unidos como aronia)- pode ser uma tarefa complicada.

Polifenóis

Estudos anteriores revelaram que compostos encontrados nas frutas, ospolifenóis, protegem o coração e impedem o entupimento das artérias.

Os cientistas franceses decidiram então testar o efeito antioxidante de diferentes misturas de sucos de frutas.

Segundo os pesquisadores da Universidade de Estraburgo, o coquetel de sete frutas mais efetivo testado por eles aumentaria o fluxo de sangue para o coração, garantindo um melhor equilíbrio entre nutrientes e oxigênio.

O estudo, publicado no periódico Food and Function, também descobriu que alguns polifenóis são mais potentes que outros e que sua capacidade de eliminar radicais livres que podem danificar células e DNA é mais importante que a quantidade de polifenóis encontrada em cada fruta.

Frutas e legumes para o coração

Tracy Parker, da organização British Heart Foundation, diz que a pesquisa confirma a evidência de que o consumo de frutas e legumes reduz o risco de doenças cardíacas, mas faz uma ressalva.

"Nós ainda não entendemos por que, ou se, algumas frutas e legumes são melhores que outros. Mesmo este estudo admite que os cientistas não conseguiram estabelecer nenhuma ligação", diz ela.

"O que sabemos é que devemos comer uma boa variedade de frutas e legumes como parte de uma dieta balanceada, e suco de fruta é uma maneira prática e gostosa de fazer isso. Mas precisamos lembrar que sucos contêm menos fibras e mais açúcar que a fruta original."

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

09:03

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

DNA from Common Stomach Bacteria Minimizes Effects of Colitis, Study Says

ScienceDaily (May 6, 2011) — DNA fromHelicobacter pylori, a common stomach bacteria, minimizes the effects of colitis in mice, according to a new study by University of Michigan Medical School scientists.

The study published in Gut this month was performed by a team of investigators assembled by senior author John Y. Kao, M.D. of the University of Michigan's Division of Gastroenterology and assistant professor in U-M's Department of Internal Medicine. The findings indicate that DNA from H. pylorisignificantly ameliorates the severity of colitis, say lead authors Jay Luther, M.D. and Stephanie Owyang, an undergraduate student on the team.

Colitis involves inflammation and swelling of the large intestine that leads to diarrhea and abdominal pain. Approximately 3.3 million people in the U.S. suffer from colitis.

More than half of the people in the world are infected with H. pylori, although only about 20 percent of U.S. residents have it. In the U.S., H. pylori infection is treated in patients with stomach ulcers or cancers with antibiotics, but the majority of infected individuals don't notice they have it and may not develop ulcers or cancers. "This research shows further evidence that we should leave the bugs alone because there may be a benefit to hosting them in the stomach," says Kao.

"H pylori has co-existed with the human race for more than 50,000 years and although it is linked with peptic ulcer disease and stomach cancer, only a minority of infected patients will develop those complications," says Luther, adding that less than 15 percent of H. pylori-infected patients develop peptic ulcer disease and less than 1 percent develop cancer.

The researchers aren't advocating infecting people with H. pylorito treat colitis, but say this may indicated that those already carrying the bacteria should not be treated unless they develop symptoms. These findings also raise significant concerns about global vaccination against H. pylori.

"This bug could be good for you, and we need to understand better what it does," says Owyang.

The H. pylori infection is more commonly found in developing countries or those with poor sanitation, where colitis, Salmonella and inflammatory bowel diseases are less common. Most people contract H. pylori in their first seven years of life, most commonly through an oral-fecal route.

In the study, researchers found that H. pylori DNA is uniquely immunosuppressive containing high numbers of sequences known to inhibit inflammation. They isolated the DNA from bothH. pylori and another bacterium, E. coli, for further comparison. They found that mice receiving H. pylori DNA displayed less weight loss, less bleeding and greater stool consistency compared with mice infected with E coli DNA.

"With one dose, there was a significant difference in the bleeding and inflammation in the colon," says Luther. "However, further study is needed to define other potential protective measures that H. pylori may provide and its safety as a treatment in patients."

In previous research, U-M gastroenterologists also found thatH. pylori reduced the severity of inflammation of the colon caused by Salmonella in mice.

"It is amazing that the bacterial DNA not only directs the biological behavior of the bacteria, but also has a significant influence on gut immunity of the host. This information might have important implications down the line in our understanding of disease manifestation," says Owyang.

Additional authors: Of the U-M Medical School: Tomomi Takeuchi, Tyler S. Cole, Min Zhang, Maochang Liu, M.D., John Erb-Downward, M.D., Joel Rubenstein, M.D., MSc (also of the Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System) Anna V. Pierzchala and Jose A. Paul. Of Taipei Veterans General Hospital: Chun-Chia Chen.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

09:01

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Protein Snapshots Reveal Clues to Breast Cancer Outcomes

ScienceDaily (May 6, 2011) — Measuring the transfer of tiny amounts of energy from one protein to another on breast cancer cells has given scientists a detailed view of molecular interactions that could help predict how breast cancer patients will respond to particular therapies.

Dr Patel's group used a microscope technique known as Foerster resonance energy transfer (FRET) imaging, which allows them to measure the interactions between two proteins.At the IMPAKT Breast Cancer Conference in Brussels, Dr Gargi Patel from the Richard Dimbleby Department, King's College London, described cutting-edge research in which she and colleagues captured detailed information about protein interactions on cancer cells, and correlated that with established genetic markers for cancer spread.

In this technique, each of the proteins is labeled with a fluorescent tag --one might be labeled green and the other red, for example. A laser is used to excite one of these labels, which becomes excited and then decays back to its rest state in a specific lifetime, which the researchers define as its fluorescent lifetime.

When this label comes within a nanometer of the second label, exciting by the laser causes some of its energy to be donated to the other label, and the fluorescent lifetime of the first label becomes shorter. "In the context of our work, this process only occurs when two proteins are close enough to be interacting, and hence we can quantitate protein-protein interactions," Dr Patel explains.

In earlier work, Dr Patel's group used this technique on breast cancer cells in the lab to describe in detail the interaction between the cell-surface molecules Her2 and Her3 that is known to determine whether a cancer will respond to the drug lapatinib.

"We aim to establish a 'signature' representing functional molecular biology, by examining protein-protein interactions, and to correlate this signature with established prognostic gene signatures and clinical and radiological data to predict patient outcome in terms of likelihood of recurrence and response to treatment such as lapatinib," Dr Patel explains. "The results we present at IMPAKT are the start of this work."

"The work I am doing captures images of the molecular state of Her2-Her3 receptors as a dimer, and shows us the results of lapatinib treatment. We have also identified a specific mutation in Her2, which reduces dimerization and the lapatinib effect. We can test tumor samples for this Her2 mutation, which would confer resistance to treatment."

This technology could have a significant clinical impact, the researchers say, by improving the accuracy of predictions about a cancer's risk of spread or response to treatment.

"Currently our methods of prognosis estimation depend on clinical data such as tumor size and lymph node status, or upon correlation with genetic signatures which may delineate tumors with higher metastatic potential. However the accuracy of any single method is far from 100%. We aim to add to the tools available by introducing a signature reflecting the functional state of cancer cells, by assessing protein-protein interactions. We could integrate this information with genetic and clinical data to more accurately predict outcome," Dr Patel said.

Commenting on the study, which he was not involved in, Dr Stephen Johnston, from Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust & Institute of Cancer Research, noted: "Lapatinib is a novel drug to target Her2 positive breast cancer, and works in a different way to the established monoclonal antibody trastuzumab."

"It is recognized that other growth factor receptors in breast cancer such as Her3 can modulate how Her2 positive tumors respond, often making them resistant to trastuzumab. In contrast, these researchers have developed as assay to measure Her2/Her3 heterodimers and the molecular pathways that they activate in human tumors, and suggest that in future this assay could be used to predict for response to lapatinib in the clinic."

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

08:59

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Universal Signaling Pathway Found to Regulate Sleep

ScienceDaily (May 6, 2011) — Sleeping worms have much to teach people, a notion famously applied by the children's show "Sesame Street," in which Oscar the Grouch often reads bedtime stories to his pet worm Slimy. Based on research with their own worms, a team of neurobiologists at Brown University and several other institutions has now found that "Notch," a fundamental signaling pathway found in all animals, is directly involved in sleep in the nematode C. elegans.

"This pathway is a major player in development across all animal species," said Anne Hart, associate professor of neuroscience at Brown. "The fact that this highly conserved pathway regulates how much these little animals sleep strongly suggests that it's going to play a critical role in other animals, including humans. The genes in this pathway are expressed in the human brain."

The work, to be published May 24 in the journal Current Biology, offers new insights into what controls sleep. The lead authors are Komudi Singh, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Neuroscience at Brown University, and Michael Chao, a previous member of the Hart laboratory, who is now an associate professor at California State University-San Bernardino.

"We understand sleep as little as we understand consciousness," said Hart, the paper's senior author. "We're not clear why sleep is required, how animals enter into a sleep state, how sleep is maintained, or how animals wake up. We're still trying to figure out what is critical at the cellular level and the molecular level."

Ultimately, Hart added, researchers could use that knowledge to develop more precise and safer sleep aids.

"We only have some really blunt tools that we can use to change sleep patterns," she said. "But there are definite side effects to manipulating sleep the way we do now."

Mysterious napping

Hart first realized that Notch pathway genes might be important for sleep when her group was investigating an entirely different behavior. She was studying the effect of this pathway on the nematodes' revulsion to an odious-smelling substance called octanol. What she found, and also reports in the Current Biology paper, is that adult nematodes without Notch pathway genes (like osm-11) have their Notch receptors turned off and, therefore, they do not avoid octanol as normal worms do.

But she was shocked to find that the adult nematodes in which the osm-11 gene was overexpressed were doing something quite bizarre. "Normally, adult nematodes spend all of their time moving" she said. "But, these animals suddenly start taking spontaneous 'naps.' It was the oddest thing I'd seen in my career."

Nematode sleep is not exactly the same as sleep in larger animals, but these worms do go into a quiescent sleep-like state when molting. The worms with too much osm-11 were dozing when they were not supposed to.

Other experiments showed that worms lacking osm-11 and the related osm-7 genes were hyperactive, exhibiting twice as many body bends each minute as normal nematodes.

The story became clear. The more Notch signaling was turned on, the sleepier the worms would be. When it is suppressed, they go into overdrive and become too active.

In humans, the gene that is most similar to osm-11 is called Deltalike1 (abbreviated DLK1). It is expressed in regions of the brain associated with the sleep-wake cycle.

Beyond Notch

That result alone is not enough to lead directly to the development of a new sleep drug, even for worms. Notch signaling is implicated in a lot of different activities in the body, Hart said, some of which should not be encouraged.

"Too much Notch signaling can cause cancer, so we would have to be very targeted in how we manipulate it," she said. "One of the next steps we're going to take is to look at the specific steps in Notch signaling that are pertinent to arousal and quiescence."

Focusing on those steps could minimize side effects, Hart said.

In addition to Hart, Singh, and Chao, other authors from Brown were Mark Corkins, Melissa Walsh, and Emma Beaumont, an intern from University of Bath. Authors who worked at Massachusetts General Hospital were Gerard Somers, Hidetoshi Komatsu, Jonah Larkins-Ford, Tim Tucey, and Heather Dionne. Author Douglas Hart is from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and author Shawn Lockery is from the University of Oregon.

The National Institutes of Health and Massachusetts General Hospital funded the research.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

08:57

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Assinar:

Postagens (Atom)