Neste Blog realizamos: 1 - Atualização sobre SAÚDE PÚBLICA, PESQUISA BIOMÉDICA E BIOSSEGURANÇA. 2 - Atualização sobre a ocorrência de Doenças de importância em animais de laboratório e outras espécies. 3 - Troca de Informações sobre Doenças Infecciosas, Zoonoses, Licenciamento Ambiental, Defesa Sanitária Animal, Vigilância Sanitária, Boas Práticas de Laboratório e demais assuntos relacionados à sanidade e Saúde Pública.

Pesquisar Neste Blog

quarta-feira, 28 de setembro de 2011

Veterinary Medicine September Issue

| ||

| ||

| ||

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:50

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

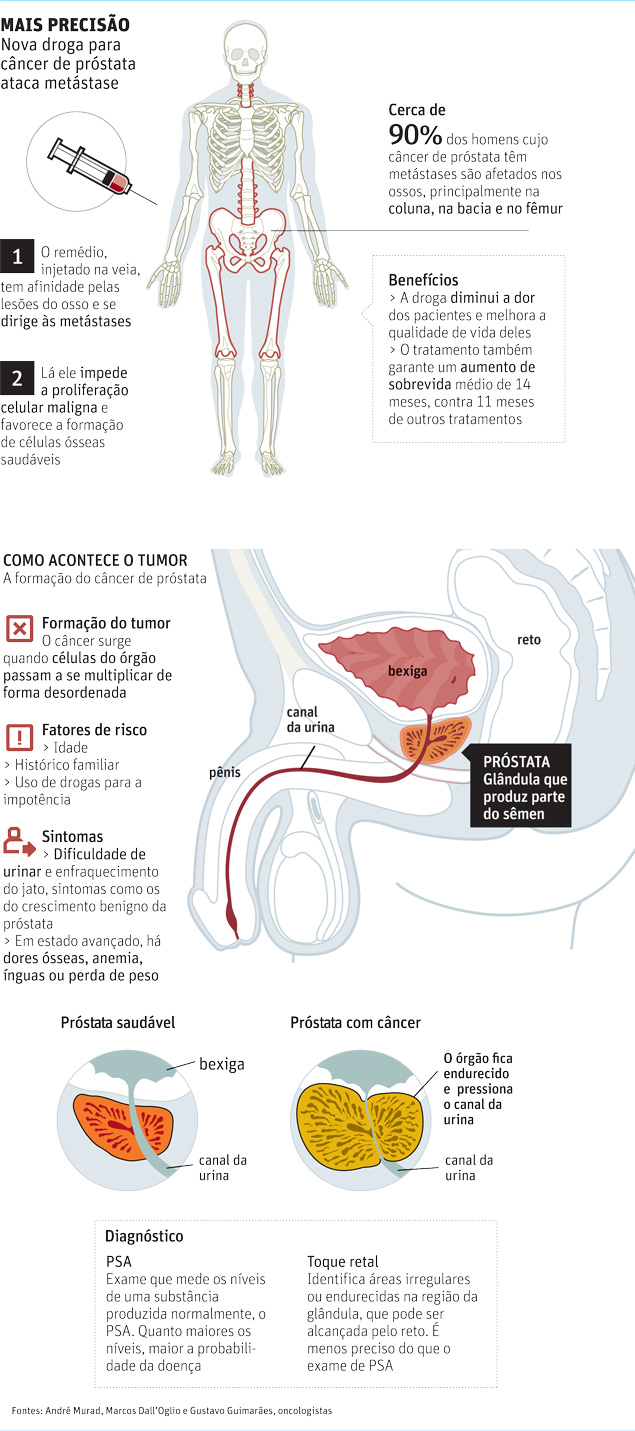

Nova droga trata câncer de próstata com metástase

Um novo medicamento para câncer de próstata em estágio avançado pode melhorar a qualidade de vida dos pacientes, diminuindo as dores, e fazê-los viverem mais.

Os resultados de estudos de fase 3 (últimos antes de uma droga ser aprovada) foram apresentados no fim de semana no congresso da Sociedade Europeia de Oncologia, em Estocolmo (Suécia).

O remédio Alpharadin foi testado em 922 pacientes com metástase óssea. Dos pacientes com câncer de próstata, até 40% têm metástase. Em 90% dos casos, o tumor se espalha para os ossos, principalmente na coluna, na bacia e no fêmur. Isso gera muita dor e pode deixar os pacientes incapazes de realizarem suas atividades diárias.

"O problema é o diagnóstico tardio. Muitos pacientes ainda têm preconceito com o exame de toque retal", afirma o oncologista André Murad, do HC da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais e do Hospital Lifecenter, que participou do estudo.

TESTE

O medicamento foi testado em 20 países, incluindo o Brasil. Seis centros médicos do país, entre eles o Hospital das Clínicas da USP e o Hospital do Câncer de Barretos, estavam envolvidos na pesquisa.

Os pacientes foram divididos em dois grupos: um deles tomava o remédio e o outro recebia placebo, sem que ninguém soubesse quem recebia o tratamento ativo.

Aqueles que tomaram o Alpharadin tiveram taxas de mortalidade 30% menores e uma sobrevida média de 14 meses, em comparação com 11 meses do outro grupo.

Como os resultados preliminares foram bons, o estudo foi interrompido para que os pacientes do grupo-placebo recebessem a droga.

TELEGUIADO

O remédio é um radiofármaco formado por partículas radioativas que têm afinidade pelas células ósseas -da mesma forma que o iodo radioativo tem preferência pela tireoide, por exemplo.

"Essas partículas se dirigem às células da metástase, depositam-se nelas e as destroem. É quase um míssil teleguiado", compara Murad.

Segundo Gustavo Guimarães, chefe do setor de urologia do Hospital A.C. Camargo, outros radiofármacos causam diminuição de glóbulos brancos e de plaquetas, e não aumentam a sobrevida.

"Esse novo remédio é mais preciso, age milimetricamente nas células malignas."

Marcos Dall'Oglio, professor da USP e chefe do departamento de uro-oncologia do HC, afirma que a droga pode adiar a quimioterapia, o que é importante no caso de pacientes idosos, que não suportam esse tratamento. A radioterapia comum também pode afetar os tecidos normais e a produção de sangue.

Os efeitos colaterais mais comuns, segundo o estudo, foram diarreia e náusea.

O aposentado Raimundo Nonato da Fonseca, 83, de Belo Horizonte, foi um dos voluntários da pesquisa e afirma não ter tido nenhuma reação adversa ao remédio.

"Por causa das dores, não caminhava. Hoje durmo melhor, como bastante bem e estou engordando. Graças a Deus me dei bem."

A Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, que produz a droga, prevê seu lançamento no Brasil em 2013.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:42

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

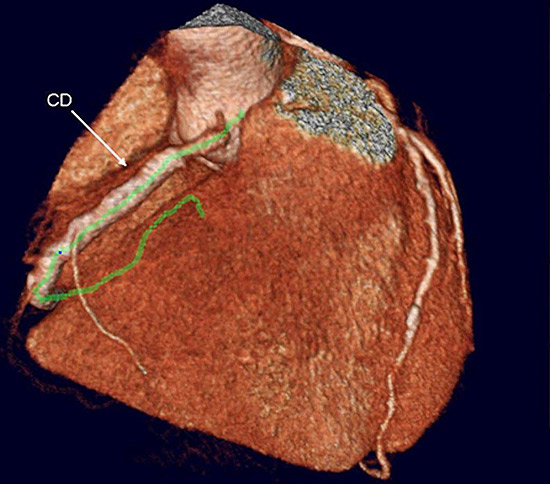

Tomografia de coronária identifica bloqueios com precisão

Um exame de tomografia coronária é muito mais preciso na detecção de obstrução das artérias do que testes laboratoriais padrão. A técnica foi aprovada em agosto pela ANS (Agência Nacional de Saúde Suplementar) e será incluída nos exames pagos por convênios a partir de janeiro de 2012.

A tomografia, que já existe há oito anos, inclusive no Brasil, pode evitar mortes por doença arterial coronária, na qual o estreitamento das veias cria obstáculos para o fluxo de sangue ao coração.

|

Tomografia de artérias coronárias em paciente com stent na artéria coronária direita(CD)

O exame é importante, porque a doença coronária mata em silêncio, explica o radiologista do InCor (Instituto do Coração), Luiz Francisco Ávila. "Mesmo indo ao médico e fazendo os exames convencionais, o paciente não vê a doença. Ela só aparece quando 70% do vaso está obstruído."

Testes laboratoriais, de esforço ou ecocardiograma não detectam obstruções se até 60% da artéria estiver bloqueada.

De acordo com o radiologista, 68% dos infartos acontecem com uma placa menor que 50%, ou seja, exames convencionais não detectariam o risco de parada cardíaca.

"Antes era difícil fazer imagens das artérias coronárias, pois era muito rápida a passagem do contraste. Como o coração batia, a imagem ficava toda mexida", explica Ávila.

O desenvolvimento de um aparelho chamado multidetector aumentou a velocidade da máquina, o que possibilita injetar o contraste e adquirir a imagem da artéria rapidamente.

Um dado alarmante mostra que metade dos 1,2 milhão de norte-americanos que tem síndrome coronariana aguda por ano, tem como primeira manifestação da doença a morte súbita.

"Normalmente, o paciente não teve nem dor no peito, nem cansaço, nem arritmia", diz.

O médico ainda explica que os pacientes que tem uma obstrução pequena na artéria morrem porque a placa se rompe e ele infarta.

"A tendência hoje na cardiologia é cada vez mais utilizar esse método."

Ele afirma que o único método que permite ver desde 1% de placa é a tomografia coronária. "O médico vê a placa enquanto ela está dentro da parede do vaso, antes dela migrar e começar a obstruir."

Ávila diz que hoje são feitas 200 tomografias de coronária por dia, em média, em São Paulo. Os aparelhos são usados tanto na rede pública como na rede privada.

O exame é feito, principalmente, para descartar a hipótese de doença coronária. Com a imagem da artéria, o paciente pode saber se deve tomar medidas de precaução, como diminuir o colesterol, praticar esportes e parar de fumar.

Outra vantagem é o tempo de duração que separa o exame do resultado: dez minutos.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:37

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Você quer viver até os 150 anos?

Delírios

O professor George Church, da Universidade de Harvard, teve seus quinze minutos de fama esta semana ao afirmar que os humanos viverão de 120 a 150 anos.

Ele não foi o primeiro a dizer isto, e certamente não será o último.

O geneticista Aubrey de Grey, por exemplo, diz não apenas que o homem viverá 150 anos, mas que o primeiro humano que viverá 150 anos já nasceu.

E ele vai além: para Grey, a primeira pessoa que viverá 1.000 anos nascerá nos próximos 20 anos.

Em alguns casos, como no de Church, é difícil separar o que é previsão científica daquilo que é entusiasmo adolescente - em um homenzarrão de quase dois metros de altura e mais de 50 anos - ou daquilo que é simples anseio de fama.

No caso de Grey, a separação do joio do trigo é bem mais fácil, porque é difícil enxergar algum trigo.

Expectativa de vida

Mas a discussão encerra temas interessantes, de grande interesse para toda a sociedade.

A expectativa de vida do homem moderno é cerca do dobro da expectativa de vida de um europeu durante a Idade Média. De 1970 a 2005, duplicou a probabilidade de uma pessoa com 65 anos chegar aos 85 anos.

Os progressos no campo da higiene, da alimentação e dos tratamentos médicos têm tido resultados entusiasmantes, o que nos faz ver a afirmação de que o homem viverá 150 anos no futuro como algo quase óbvio.

Contribuições da genética

Apesar do grande apelo na mídia, contudo, a genética ainda não produziu resultados nesta área.

A anunciada descoberta de um "gene da longevidade", por exemplo, já foi devidamente desmentida.

Mas isto é temporário e, de fato, espera-se que a genética dê resultados na área da longevidade, embora já se saiba que o DNA não tem todas as respostas.

Mas a discussão principal não é quantos anos a mais viveremos, mas como os viveremos.

Viver mais doente

A onda de privatizações que dominou o mundo nos anos 1980 e 1990 praticamente deixou todo o desenvolvimento de medicamentos nas mãos de empresas privadas. Exemplos como os da Fiocruz no Brasil são cada vez mais raros.

Como empresas privadas precisam de lucros constantes, nos anos recentes a chamada "Big Pharma" centrou todos os seus esforços em medicamentos de uso contínuo, porque medicamentos para doenças crônicas garantem lucros continuados.

Desta forma, o foco do desenvolvimento de medicamentos atualmente não está em "curar doenças", mas em fazer o paciente viver mais, ainda que seja em uma cama de hospital ou em uma vida parcial dentro de casa.

Uma pesquisa recente, realizada nos Estados Unidos, onde o acesso à saúde é muito mais homogêneo entre a população, mostrou que, apesar de estarem vivendo mais, as pessoas estão passando um percentual maior de suas vidas doentes.

"Nós temos assumido que cada geração será mais saudável e viverá mais do que a anterior. No entanto, a pressão da morbidade pode ser tão ilusória quanto a imortalidade," afirmou o Dr. Eileen Crimmins, da Universidade da Califórnia.

E isto nem vale para toda a população porque restou um monte de doenças negligenciadas pelas grandes empresas farmacêuticas, para as quais sobra o esforço de um grupo de cientistas abnegados, que nunca conseguem colocar suas descobertas no mercado porque as instituições públicas das quais fazem parte não têm a estrutura necessária para a comercialização.

Mas, ao menos estes grupos fazem um trabalho de verdadeiros cientistas, em busca de curas para os doentes, em vez de repetidos lucros para suas empresas à custa de decisões eticamente discutíveis.

Um trabalho bem mais digno do que simplesmente ficar tentando chamar a atenção para si próprios, como os "divulgadores da imortalidade" fazem.

É esta classe de cientistas que nos permitirá, no futuro, viver 150 anos de fato, como pessoas ativas e com qualidade de vida.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:33

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Researchers Uncover Gene Associated With Blood Cancers; New Genetic Insights Could Facilitate Screening for Mutation

ScienceDaily (Sep. 27, 2011) — A genomic study of chronic blood cancer -- a precursor to leukemia -- has discovered gene mutations that could enable diagnosis using only a blood test, avoiding the need for an invasive and painful bone marrow biopsy.

Researchers at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute identified the SF3B1 gene as being frequently mutated in myelodysplasia, one of the most common forms of blood cancer. Myelodysplasia is particularly prevalent among people over the age of 60, and often the only symptom is anemia, which makes it a challenge to give a positive diagnosis. Patients with mutations in the SF3B1 gene frequently had a specific abnormality of red blood cells in their bone marrow, called ring sideroblasts.

The findings have significant potential for clinical benefit, as the disease is often under-diagnosed. It is hoped that patients will soon be able to be screened for mutations in the SF3B1 gene through a single blood test.

"This discovery illustrates the promise of genome sequencing in cancer," says Dr Elli Papaemmanuil, lead author from the Sanger Institute. "We believe that by identifying SF3B1, and working to characterize the underlying biology of this disease, we will be able to build improved diagnosis and treatment protocols.

"Significantly, our analysis showed that patients with the SF3B1 mutation had a better overall chance of survival compared to those without the mutation. This suggests that the SF3B1 mutations drive a more benign form of myelodysplasia."

In order to piece together the genomic architecture of myelodysplasia, the team sequenced all genes in the genome of nine patients with the disease. To their surprise, six had mutations in the SF3B1 gene. To expand their analysis, the researchers sequenced the SF3B1 gene in 2,087 samples across many common cancers.

In myelodysplasia, SF3B1 mutations were found in 20.3 per cent of all patients, and in 65 per cent of those patients with ring sideroblasts, making it one of the most frequently mutated genes so far discovered in this disease. Researchers found mutations of the same gene in up to 5 per cent of a range of other common cancers, such as other leukemias, breast cancer and kidney cancer.

"Anemia affects 1 in 10 people over the age of 65, and we cannot easily find a cause for the anemia in a third of cases," says Peter Campbell, senior author, from the Sanger Institute and a practicing Haematologist at Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge. "To diagnose myelodysplasia, we often have to resort to an invasive and painful bone marrow biopsy, but we hope this and future genetic insights will provide more straightforward diagnosis for patients through a simple blood test."

"Ever since I first saw these unusual and damaging blood cells -- ring sideroblasts -- down the microscope while training to become a haematologist, I have been fascinated by them and determined to find a cause. To discover a major genetic clue to their origins is very exciting, and I look forward to piecing together how the mutations cause these curious cells to develop and lead to this disease."

The SF3B1 gene encodes a core component of RNA splicing, an important editing mechanism that controls how the genome's message is delivered to the cell. The team discovered a strong association between the gene and the presence of ring sideroblasts, making it the first gene to be strongly associated with a specific feature of the disease. Ring sideroblasts are abnormal precursors to mature red blood cells with a partial or complete ring of iron-laden mitochondria (energy generators) surrounding the nucleus of the cell. Their presence is frequently associated with anemia.

"These genetic discoveries are very important and could potentially assist clinicians when diagnosing blood cancers in patients, avoiding the need for invasive bone marrow biopsies. Myelodysplasia is becoming increasingly prevalent in people over 60, and cases will continue to rise with our increasing aging population, particularly among those who suffer from anemia," says Dr David Grant, Scientific Director at Leukaemia & Lymphoma Research. "We are delighted to have supported research into the genomic architecture of myelodysplasia which will contribute towards making a difference for the diagnosis and treatment for patients."

The study was a project for the International Cancer Genome Consortium, a forum for collaborations among the world's leading cancer and genomic research.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:30

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Discovery of Insulin Switches in Pancreas Could Lead to New Diabetes Drugs

ScienceDaily (Sep. 27, 2011) — Researchers at the Salk Institute have discovered how a hormone turns on a series of molecular switches inside the pancreas that increases production of insulin.

The finding, published September 26 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, raises the possibility that new designer drugs might be able to turn on key molecules in this pathway to help the 80 million Americans who have type 2 diabetes or pre-diabetic insulin resistance.

The molecular switches command pancreatic beta islet cells, the cells responsible for insulin, to grow and multiply. Tweaking these cells might offer a solution to type 1 diabetes, the form of diabetes caused by destruction of islet cells, and to type II diabetes, the form caused by insulin resistance.

"By understanding how pancreatic cells can be encouraged to produce insulin in the most efficient way possible, we may be able to manipulate those cells to treat or even prevent diabetes," says the study's lead author, Marc Montminy, a professor in the Clayton Foundation Laboratories for Peptide Biology at Salk.

Such new agents might increase the functioning of beta islet cells even in people who have not developed diabetes.

"The truth is that as we grow older, these islet cells tend to wear out," Montminy says. "The genetic switches just don't get turned on as efficiently as they did when we were younger, even if we don't develop diabetes. It's like using a garage door opener so many times, the battery wears out. We need a way to continually refresh that battery."

Type II diabetes is caused by an inability for insulin to stimulate muscles to take up glucose, a kind of sugar, from the bloodstream after eating. Age is a risk factor for diabetes, as is obesity, genetic predisposition and lack of physical exercise.

Montminy and two researchers in his lab, Sam Van de Velde, a post-doctoral research associate, and Megan F. Hogan, a graduate student, set out to study how glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), a hormone produced in the gastrointestinal tract, promotes islet cell survival and growth.

The question is important, not only to understanding basic insulin biology, but also because it would help explain how a drug approved to treat diabetes in 2005 actually works.

That drug, exenatide (Byetta), is a synthetic version of extendin-4, a hormone found in the saliva of the Gila monster lizard. Extendin-4 is similar to GLP-1 in humans, but is much longer acting. "The Gila monster hibernates most of its life, feeding only twice a year, so it needs a way of storing food really well, which means its insulin has to be very efficient," says Montminy.

GLP-1 has a very short duration because enzymes in the bloodstream break it down quickly after it activates insulin production, he says. Patients using exenatide, on the other hand, need to inject it only twice a day.

As helpful as that drug is, Montminy reasoned that if he could pinpoint the various switches that GLP-1 turns on to promote insulin secretion, it might be possible to identify drug targets that might be even more efficient for human use than exenatide.

The researchers set out to identify the various players in the molecular pathway that is activated when GLP-1 docks onto its receptor on the surface of islet cells. In his previous work, Montminy had already discovered that one of the first switches activated is CREB, which turns on other genes.

In this study they defined other players "downstream" of CREB -- discoveries that turned out to be surprising. Two of the molecules, mTOR and HIF, are heavily implicated in cancer development, Montminy says. For example, mTOR is a critical sensor of energy in cells, and HIF works inside cells to reprogram genes to help cells grow and divide.

"Turning on switches inside a cell is a bit like running a relay race," Montminy says. "GLP-1 activates CREB, which passes the baton to mTOR, and then HIF takes over to help islet cells withstand the stresses that cause wear and tear, such as aging. It stands to reason that mTOR and HIF would be involved in helping islet cells to remain healthy because they are involved in cell growth -- in this case, growth of islet cells."

These findings suggest it may be possible to activate these molecular players independently to restore insulin production, Montminy says. A drug could directly activate the HIF switch, for example, bypassing the prior steps in the pathway: GLP-1, CREB and mTOR. That might not only increase production of insulin from existing islet cells, but also promote growth of new islet cells.

The findings have other clinical implications as well. Understanding that mTOR is involved in insulin secretion helps explain why some transplant patients develop diabetes. Rapamycin, a drug often used to prevent organ rejection, suppresses mTOR activity, and so probably undermines insulin production.

Knowing that activating HIF also may help islet cells grow could be useful in efforts to transplant islet cells in patients with type 1 diabetes.

The study was funded by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Keickhefer Foundation, the Clayton Foundation for Medical Research, the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and by Charles Brandes.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:29

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Tracing an Elusive Killer Parasite in Peru

cienceDaily (Sep. 27, 2011) — Despite what Hollywood would have you believe, not all epidemics involve people suffering from zombie-like symptoms--some can only be uncovered through door-to-door epidemiology and advanced mathematics.

|

Triatomine insect vector of parasite that causes Chagas disease.

|

Michael Levy, PhD, assistant professor of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, along with other collaborators from Penn, Johns Hopkins University, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia in Peru, are in the trenches combining tried-and-true epidemiological approaches with new statistical methods to learn more about the course of a dangerous, contagious disease epidemic. Their research was published recently inPLoS Computational Biology.

Chagas disease, primarily seen in South America, Central America, and Mexico, is the most deadly parasitic disease in the Americas. Caused by the protozoan parasite, Trypanosoma cruzi, it is spread chiefly via several species of blood-sucking triatomine insects. After an initial acute phase, the disease continues to lurk in the body and can eventually cause a variety of chronic life-threatening problems, particularly in the heart. Although there are some drugs to treat Chagas disease, they become less effective the longer a person is infected. The lack of a vaccine also means that the only effective way to control the disease is to control the disease vectors.

Because the chronic effects of Chagas disease can take decades to manifest themselves, tracking the development and progression of epidemics has been a challenging problem. In the past, Chagas disease was known mostly in rural regions, but has been spreading into more urbanized areas over the last 40 years. Levy's team has been focusing on one of those areas in the city of Arequipa, Peru.

"There is an assumption that Chagas disease is not a problem in Peru because statistics don't show that more people are dying of cardiac disease in the areas with Chagas transmission compared to the rest of the country," Levy said. "What we've shown calls into question the assumption that the particular parasite that's circulating in Arequipa is somehow less virulent. We show that there's really nothing to back that assumption."

Epicenter Regression

The researchers used epicenter regression, which takes a statistical "snapshot" of disease infection in a particular population to track the history of how an infection takes hold and spreads. Epicenter regression considers the duration of an individual's exposure to infection as a function of distance from their home to an unknown site, or sites, where disease has been introduced, and combines that measure with other known risks to estimate the probability of infection. From this data, the course of infection can be traced backward to infer where and when a disease first struck a community.

Levy's team has been collecting data in Peru since 2004. "We do all the fieldwork, we gather all our data, which is very much door-to-door, old-fashioned epidemiology," said Levy. That involves both entering households to search for infected insects and collecting blood samples from residents. The team's survey work led to the observation of spatial clusters of parasites in insects such that "it looked like there were isolated clusters of transmission, or 'micro-epidemics.' It was really observation, then hypothesis, then testing."

According to their findings, the Chagas parasite was introduced into the region about twenty years ago, and most infections occurred over the last ten years. Spread of the disease is being disrupted in Arequipa through insecticide application, but up to 5 percent of the population was infected before their houses were sprayed with insecticide. Levy and his colleagues conclude that the lack of chronic disease symptoms among these infected individuals could be due to the relatively short time of transmission: Most individuals may have yet to pass from the long asymptomatic period to symptomatic Chagas disease.

Inevitable Increase

The finding has crucial implications for the future management of the disease. Because the lack of late-stage Chagas disease in Arequipa is not an indication of a weakened parasite, the researchers believe that preparations should be made for a potential increase in chronic Chagas cases in coming years. As they have throughout their research, Levy's team is working in close collaboration with the Peruvian government to ensure that the warning provided by their work does not go unheeded. "Everything we do in Arequipa is with the local Ministry of Health," Levy said. "We're very much integrated with the government's Chagas disease control program. We started diagnosing people who are asymptomatic and the Ministry of Health is treating the individuals who are diagnosed to increase the probability they don't progress to later-stage disease."

Levy and his collaborators, including Eleazar Cordova-Benzaquen and Cesar Naquira in Peru, plan to expand their epicenter regression modeling techniques to study other infectious diseases, including the West Nile virus in New York City. The method can even be applied to fighting the spread of pesky insects such as bedbugs. "We're trying to work in parallel to improve control of Chagas vectors and bedbugs," he noted. "The idea is if you find a house with bedbugs, where do you go next? Same thing with the Chagas bugs. When they come back after the insecticide campaigns, you get a report and you have to figure out how to react to those reports, which are pretty scattered." Levy and his team have found a way to find patterns, and thus more predictability, in the chaos of infectious disease transmission.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:27

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Assinar:

Comentários (Atom)