The research, published in the November 11 issue of the journalCell, reveals a new and previously unsuspected role for nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR), a transcriptional coregulatory protein found in a wide variety of cells.

"Different transcription factors stimulate genes, turning them on and off, by bringing in co-activators or co-repressors," said Jerrold M. Olefsky, MD, associate dean for Scientific Affairs and Distinguished Professor of Medicine at UC San Diego and senior author of the paper. "All transcriptional biology is a balance of these co-activators and co-repressors."

Olefsky and colleagues focused their attention on NCoR, which was known to be a major co-repressor of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor gamma or PPAR-gamma, a ubiquitous protein that regulates fatty acid storage and glucose metabolism, but which also appeared to act on other receptors as well.

"It seemed to be a general purpose co-repressor," said Olefsky. "It's unusual for one protein to do so many things. It's not very efficient and you don't see it too much in biology."

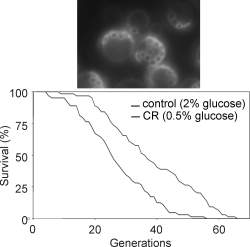

The scientists created a knock-out mouse model whose adipocytes or fat cells lacked NCoR. Though bred to be obese and prone to diabetes, Olefsky said the glucose tolerance improved in the NCoR knock-out mice. Moreover, they displayed enhanced insulin sensitivity in liver, muscle and fat, and decreased systemic inflammation. Resistance to insulin, a hormone central to regulating carbohydrate and fat metabolism, is a hallmark of diabetes, as is chronic inflammation.

"When NCoR was deleted, insulin sensitivity in the whole animal increased dramatically compared to normal obese mice, which remained insulin resistant. The sensitivity occurred not just in adipocytes, but in all cells," said Olefsky. "With NCoR knocked out of adipocytes, PPAR-gamma becomes active. This produces a robust increase in systemic insulin sensitivity."

Phosphorylation is a biochemical process in which a phosphate group is added to a protein or other organic molecule, activating or deactivating many protein enzymes. It turns out that NCoR facilitates phosphorylation of PPAR-gamma, so that without NCoR, the receptor remains unphosphorylated and active.

In related work also published in the same issue of Cell, EPFL scientists found that knocking out NCoR in muscle cells produced a surprising effect. It did not repress PPAR-gamma, but rather generated a different phenotype or set of results.

"In adipocytes, NCoR repressed PPAR-gamma, but in other cells, it appears to repress other transcription factors," Olefsky said. "That's a new principle: A repressor that's found in many cells, but performs a specific, different function depending on the cell type."

Though NCoR's role as a major co-repressor was known, it was considered a poor drug target because inhibiting it could cause unwanted de-repression in some cell types, producing adverse side effects. Olefsky said the newly discovered specificity of NCoR revitalizes the idea that NCoR may be an excellent drug target for type 2 diabetes and other insulin resistant diseases.

"If researchers can make a drug that's tissue-specific, repressing NCoR could be a powerful way to boost insulin sensitivity. It's doable. Already, we can create drugs that specifically target fat and liver cells. That might be good enough to produce a system-wide benefit."

Co-authors of the study are Pingping Li, WuQiang Fan, Jianfeng Xu, Min Lu, Dorothy D. Sears, Saswata Talukdar, DaYoung Oh, Ai Chen, Gautam Bandyopadhyay, Jachelle M. Ofrecio and Sarah Nalbandian of the Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, UC San Diego; Hiroyasu Yamamoto and Johan Auwerx of the Laboratory of Integrative and Systems Physiology, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne and Miriam Scadeng, Department of Radiology, UC San Diego.

Funding for this study came, in part, from the National Institutes of Health, the EU Ideas Program, the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development as part of the specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research.