Neste Blog realizamos: 1 - Atualização sobre SAÚDE PÚBLICA, PESQUISA BIOMÉDICA E BIOSSEGURANÇA. 2 - Atualização sobre a ocorrência de Doenças de importância em animais de laboratório e outras espécies. 3 - Troca de Informações sobre Doenças Infecciosas, Zoonoses, Licenciamento Ambiental, Defesa Sanitária Animal, Vigilância Sanitária, Boas Práticas de Laboratório e demais assuntos relacionados à sanidade e Saúde Pública.

Pesquisar Neste Blog

sexta-feira, 25 de março de 2011

Companion Animal Content Alert: 16, 2 (March 2011) - Volume 16, Issue 2 Pages 3–66

2044-3862/asset/olbannerright.jpg?v=1&s=33ae3c8c6fa205fb72f5aec8e3ba5416dec17acc) * Editorial

* EditorialEditorial (page 3)

Article first published online: 25 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3862.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

* EQUINE

** MEDICINE

Clinical Refresher: Equine sinus cyst (pages 4–6)

Safia Barakzai

Article first published online: 25 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3862.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

** OPHTHALMOLOGY

Equine Fungal Keratitis: A case report (pages 8–12)

Pedro Malho

Article first published online: 25 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3862.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

* SMALL ANIMAL

** SMALL ANIMAL REVIEW

SMALL ANIMAL REVIEW (page 13)

Article first published online: 25 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3862.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

** SURGERY

Making sense of cranial cruciate ligament disease Part 2: Diagnosis (pages 14–18)

Greg Harasen

Article first published online: 25 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3862.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

** OPHTHALMOLOGY

Dacryocystitis in Rabbits (pages 19–21)

Sarah Cooper

Article first published online: 25 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3862.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

** IMAGING

Canine imaging self‐assessment (pages 25–28)

Avi Avner

Article first published online: 25 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3862.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

** MEDICINE

Canine medicine self‐assessment (pages 30–34)

Audrey K. Cook and Brier Bostrom

Article first published online: 25 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3862.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

The role of parasites in puppy diarrhoea: the usual suspects (pages 35–39)

Ian Wright

Article first published online: 25 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3862.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

** DERMATOLOGY

Pedal dermatitis Part 2: Canine pododermatitis (pages 41–46)

Adri van den Broek and Christa Horvath‐Ungerboeck

Article first published online: 25 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3862.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

Louse infestation (pediculosis) in pet animals (pages 49–53)

Mark Craig

Article first published online: 25 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3862.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

** ANAESTHESIA

Local anaesthesia/analgesia of the limbs (pages 55–60)

Jacqueline C Brearley

Article first published online: 25 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3862.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

** EQUIPMENT REVIEW

Equipment review: Companion therapy laser CTL‐6 and CTL‐10 (pages 61–66)

Carl Gorman

Article first published online: 25 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3862.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

Livestock Content Alert: 16, 2 (March/April 2011) -

2044-3870/asset/olbannerright.jpg?v=1&s=b0c92240c8fe659ad63c4fe6c211f39ae52994eb) * EDITORIAL

* EDITORIALEditorial (page 3)

Article first published online: 24 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3870.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

* ORIGINAL ARTICLES

UK Disease Profile Compiled from NADIS data (pages 4–13)

Article first published online: 24 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3870.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

* CATTLE

CATTLE REVIEW (page 14)

Article first published online: 24 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3870.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

Fatty liver and displaced abomasums in a TMR‐fed dairy herd (pages 15–18)

James Husband

Article first published online: 24 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3870.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

Suspected congenital pseudomyotonia in two Scottish beef herds (pages 19–22)

Phil Scott

Article first published online: 24 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3870.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

A systematic approach to calf Gastroenteric disease (pages 23–28)

Tim Potter

Article first published online: 24 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3870.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

Long standing lameness problem in a dairy herd (pages 29–33)

Andrew White

Article first published online: 24 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3870.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

Cattle self‐assessment (pages 34–36)

James Breen, Chris Hudson and Paula Wilson

Article first published online: 24 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3870.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

* SHEEP

Uterine torsion in the ewe (pages 37–39)

Phil Scott

Article first published online: 24 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3870.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

* PIG

Porcine respiratory disease complex (PRDC) (pages 40–42)

Mark White

Article first published online: 24 MAR 2011 | DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-3870.2010.

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.

Mapeamento genético ajuda a entender causas do câncer de sangue

Um estudo publicado pela revista britânica "Nature" mostra a relação mais completa já estabelecida entre os prováveis fatores genéticos que provocam o mieloma múltiplo, uma forma comum de câncer de sangue, na qual os leucócitos (células brancas) se multiplicam excessivamente.

O mapeamento foi feito a partir de pesquisas com o DNA de 38 portadores da doença, em um estudo realizado em parceria por 21 instituições científicas da América do Norte.

As células sanguíneas brancas são produzidas na medula óssea e fabricam os anticorpos que ajudam o sistema imunológico a defender o organismo. O mieloma múltiplo ataca estas defesas, deixando os pacientes extremamente expostos a infecções.

A taxa de sobrevivência da doença é pequena se comparada a de outros tipos de câncer. Cerca de 20 mil novos casos são diagnosticados nos Estados Unidos todos os anos, e menos de 40% dos pacientes vivem por mais de cinco anos.

O sequenciamento genético olha através do código do DNA em busca de pequenas variações que poderiam explicar porque algumas pessoas correm o risco de desenvolver a doença e outras, não.

O custo do sequenciamento caiu bastante nos últimos anos, o que significa que os cientistas agora são capazes de ampliar ainda mais sua rede de conhecimentos genéticos. Estudos anteriores sobre o mieloma múltiplo, por exemplo, trabalhavam apenas sobre os dados genéticos de um único paciente.

"Pela primeira vez, nós conseguimos ver em nível molecular o que pode ser a causa deste mal", comemorou David Siegel, do John Theurer Cancer Center da Universidade de Hackensack, em New Jersey.

"Já sabemos o que provoca muitos tipos de câncer, mas até hoje tínhamos poucas pistas sobre as causas do mieloma", explicou.

Uma análise preliminar das variações do DNA sugere haver caminhos comuns --especialmente no sistema de fabricação de proteínas-- que permitem a uma célula cancerosa sobreviver, invadir e se multiplicar no organismo.

Entender mais sobre estes caminhos comuns levará os cientistas a uma compreensão maior sobre o funcionamento básico do mieloma --e, mais tarde, permitirá o desenvolvimento de medicamentos capazes de combatê-lo, esperam os pesquisadores.

"Este é um bom exemplo de como a análise genética pode ajudar a orientar o campo farmacêutico na direção certa de maneira dramática", estimou Todd Golub, diretor do programa de pesquisa do câncer no Broad Institute of Harvard University e no Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:55

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Marcadores:

Câncer

Tuberculose mata cerca de 5.000 pessoas por ano no Brasil

A tuberculose, doença passível de ser prevenida, tratada e mesmo curada, ainda mata cerca de 4.700 pessoas todos os anos no Brasil. Os dados são do Fundo Global Tuberculose Brasil, que preparou ações em todo o país para marcar o Dia Mundial de Combate à Tuberculose, lembrado nesta quinta.

A data foi criada em 1982 pela OMS (Organização Mundial da Saúde) em homenagem aos cem anos do anúncio do descobrimento do bacilo causador da tuberculose. A doença infectocontagiosa afeta principalmente os pulmões, mas também pode ser identificada em órgãos como ossos, rins e meninges (membranas que envolvem o cérebro).

Atualmente, o Brasil ocupa o 19º lugar entre os 22 países responsáveis por 80% do total de casos de tuberculose no mundo. São notificados anualmente 72 mil novos casos da doença no país. O maior desafio, segundo o fundo, é a mobilização social a partir da realização de uma agenda comum, capaz de alertar e orientar a população sobre os riscos da doença, os sintomas, a prevenção, o diagnóstico e o tratamento.

De acordo com o Ministério da Saúde, os sinais e sintomas mais frequentes são tosse seca contínua no início, com presença de secreção por mais de quatro semanas, transformando-se em uma tosse com pus ou sangue. Há ainda cansaço excessivo, febre baixa geralmente no período da tarde, sudorese noturna, falta de apetite, palidez, emagrecimento acentuado, rouquidão, fraqueza e prostração.

Alguns pacientes, entretanto, não exibem nenhum indício da doença, enquanto outros apresentam sintomas aparentemente simples, ignorados durante alguns meses ou mesmo anos.

A transmissão da tuberculose é direta, de pessoa a pessoa. O doente expele, ao falar, espirrar ou tossir, pequenas gotas de saliva que podem ser aspiradas por outro indivíduo. Pessoas com Aids, diabetes, insuficiência renal crônica, desnutridas, além de idosos doentes, alcoólatras, viciados em drogas e fumantes são mais propensos a contrair a tuberculose.

Para prevenir a doença é necessário imunizar crianças de até 4 anos --sobretudo as menores de 1 ano-- com a vacina BCG. A prevenção inclui ainda evitar aglomerações, especialmente em ambientes fechados.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:53

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Marcadores:

Tuberculose

Pesquisadores estudam capacidade evolutiva de bactérias

Desde a época de Darwin, os biólogos reconhecem a evolução da vida. Porém, nos últimos 25 anos, alguns pesquisadores argumentam que certos organismos são melhores em evoluir do que outros pelas diferenças de seus genomas.

As espécies com menos probabilidade de evoluir, em contraste, são rígidas demais para tirar vantagem das novas mutações ou para encontrar novas soluções para a sobrevivência.

Muitos biólogos concordam que a capacidade de evoluir faz sentido na teoria. No entanto, encontrar evidências no mundo natural tem se mostrado difícil.

Parte do problema é que a seleção natural pode levar um longo tempo para agir numa espécie. Também é difícil para os pesquisadores identificarem as mutações por trás da evolução.

Mas na edição mais recente da "Science", uma equipe de pesquisadores relata um exemplo detalhado sobre a capacidade evolutiva em ação, que ocorreu bem diante de seus olhos num laboratório.

"Acho um trabalho brilhante", diz um dos pesquisadores líderes sobre a capacidade evolutiva, Massimo Pigliucci, professor do Lehman College no Bronx, Nova York.

PESQUISA DESDE 1988

O novo estudo surgiu a partir do experimento contínuo mais duradouro sobre a evolução, iniciado em 1988 quando Richard E. Lenski, hoje na Universidade do Estado de Michigan, colocou em 12 frascos cópias idênticas de Escherichia coli. Ele e seus colegas cultivaram a bactéria com uma dieta escassa de glicose desde então.

Ao longo das 52 mil gerações, a bactéria se adaptou ao ambiente peculiar. A cada 500 gerações, Lenski e seus colegas congelam algumas das bactérias, que podem ser aquecidas para serem comparadas a seus descendentes evoluídos.

Lenski e seus colegas selecionaram uma das 12 linhagens para um estudo mais próximo. "Queríamos rastrear a ordem nas quais as mutações apareciam e tirar um sentido disso", conta.

Os cientistas observaram que, após 500 gerações, dois tipos de E. coli eram dominantes no frasco, cada uma com um conjunto distinto de mutações. No entanto, após mil gerações, apenas um tipo permaneceu. Lenski e seus colegas o batizaram de "ganhadores".

Eles quiseram demonstrar o curso dessa vitória sobre os perdedores e aqueceram ambos os tipos da 500ª geração, e fizeram com que competissem entre si. Os cientistas esperavam que o resultasse fosse uma conclusão inevitável: os vencedores já estariam mostrando sua superioridade. Ainda assim, o experimento foi feito em nome da exatidão.

"Queríamos colocar os pingos nos is", explica Lenski.

NÃO É O QUE PARECE

Para surpresa dos pesquisadores, eles estavam errados. Na 500ª geração, os supostos perdedores eram muito superiores, crescendo 6,5% mais rápido do que os que seriam vencedores. Nesse ritmo, eles levariam os supostos vencedores à extinção em 350 gerações.

Os cientistas viram duas possíveis explicações para essa reviravolta. Uma é que os vencedores eram mais propensos a evoluir e tinham mais potencial para aumentar seu índice de crescimento, permitindo que chegassem e ganhassem a corrida evolucionária.

A outra possibilidade é a de que os vencedores eram apenas seres de sorte: em algum momento após a 500ª geração, desenvolveram mutações benéficas que lhes trouxeram vantagem.

"Uma pessoa que não sabe jogar cartas pode ser um jogador melhor de vez em quando só por ter pego uma sequência real", ilustra Lenski.

Ele e seus colegas organizaram um novo experimento para analisar as duas possibilidades, descongeladno alguns dos vencedores da 500ª geração que foram usados para dar origem a 20 novas linhagens de bactérias. Da mesma forma, iniciaram 20 outras novas linhagens com os supostos perdedores.

A partir daí, os cientistas permitiram que todas as bactérias descongeladas se reproduzissem por 883 gerações.

Os supostos vencedores ainda derrotaram consistentemente os supostos perdedores, como descobriram os pesquisadores. Em média, eles acabaram crescendo 2,1% mais rápido que seus rivais. Em outras palavras, seu sucesso não foi resultado de boa sorte. Eles eram mais bem preparados para aproveitar ao máximo as mutações benéficas.

Os experimentos permitiram que os cientistas reconstruíssem a corrida evolucionária. Os supostos perdedores inicialmente assumiram a liderança com mutações que lhes deram um aumento de curto prazo em seu ritmo de crescimento.

Porém, essas mutações levaram a uma derrota no longo prazo porque, quando as mutações benéficas adicionais apareceram, os perdedores tiveram apenas um pequeno aumento em seu ritmo de crescimento. Os ganhadores, por outro lado, apresentaram maior benefício com mutações posteriores, permitindo que abrissem vantagem e dominassem o frasco.

Pigliucci afirma que a capacidade evolutiva poderia explicar vários importantes padrões na natureza, como por que alguns animais possuem muitas formas diferentes, enquanto seus parentes próximos não mudaram muita coisa em centenas de milhões de anos.

Isso significaria que a capacidade de evoluir precisaria estar presente na luta pela sobrevivência geração após geração. E o experimento de Lenski documenta que isso pode, de fato, fazer a diferença para organismos reais.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:42

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Marcadores:

Bactérias

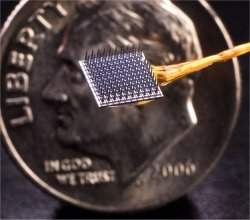

Chip neural completa 1.000 dias implantado em paciente

Interface cérebro-computador

O primeiro chip neural implantado em voluntários humanos para um teste clínico acaba de completar 1.000 dias em perfeito funcionamento.

O BrainGate (portal para o cérebro, em tradução livre) está implantado em uma mulher com tetraplegia e, desde então, permite que a paciente controle um cursor na tela do computador usando apenas o pensamento.

Este é um marco importante para as interfaces cérebro-computador porque os primeiros experimentos sofriam rejeição logo após o implante - o organismo criava uma espécie de cicatriz que impedia que os eletrodos coletassem as informações do cérebro.

Controle do computador pelo pensamento

Para testar o funcionamento continuado do aparelho e estabelecer com segurança a marca dos 1.000 dias, os médicos do MIT e da Universidade Brown, nos Estados Unidos, responsáveis pelo experimento, submeteram a paciente a um teste com duração de cinco dias.

Os resultados bem-sucedidos foram publicados nesta quinta-feira no Journal of Neural Engineering.

"Essa prova de conceito - que, após 1.000 dias uma mulher que não tem nenhum uso funcional de seus membros e é incapaz de falar, pode controlar com confiabilidade um cursor na tela de um computador usando apenas a intenção do movimento da mão - é um marco importante para o campo," disse o Dr. Leigh Hochberg.

A mulher, identificada no artigo científico apenas como S3, realizou tarefas de apontar e clicar - para isso, ela precisava apenas imaginar que sua mão está se estendendo e movendo o cursor.

A média de precisão foi superior a 90 por cento. Alguns alvos na tela eram do tamanho de ícones de programas comuns de computador.

"Nosso objetivo com a interface neural é alcançar o nível de desempenho de uma pessoa sem deficiência usando um mouse", disse o principal autor do relatório, Simeral John.

BrainGate

Em desenvolvimento desde 2002, o sistema BrainGate é uma combinação de hardware e software que detecta diretamente no cérebro sinais elétricos produzidos pelos neurônios que controlam o movimento.

O aparelho decodifica esses sinais e os traduz em instruções digitais que são passadas ao computador.

O BrainGate está sendo avaliado em sua capacidade de dar às pessoas com paralisia o controle de dispositivos externos, tais como computadores, dispositivos de assistência robótica ou cadeiras de rodas.

A equipe também está envolvida em outra pesquisa para o controle de próteses avançadas e para o controle intracortical direto de aparelhos de eletroestimulação funcional para pessoas com lesão na medula.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:25

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Marcadores:

Cérebro

Prostate Cancer Spreads to Bones by Overtaking the Home of Blood Stem Cells

ScienceDaily (Mar. 24, 2011) — Like bad neighbors who decide to go wreck another community, prostate and breast cancer usually recur in the bone, according to a new University of Michigan study.

|

This is a drawing of prostate cancer cells in the bone marrow niche. |

Now, U-M researchers believe they know why. Prostate cancer cells specifically target and eventually overrun the bone marrow niche, a specialized area for hematopoietic stem cells, which make red and white blood cells, said Russell Taichman, professor at the U-M School of Dentistry and senior author of the study.

Once in the niche, the cancer cells stay dormant and when they become active again years later, that's when tumors recur in the bone. The implication is that this may give us a window as to how dormancy and recurrence take place.

Taichman and a team of researchers looked in the bone marrow and found cancer cells and hematopoietic stem cells next to one another competing for the same place. The finding is important because it demonstrates that the bone marrow niche plays a central role in bone metastasis -- cancers that spread into the bone -- giving researchers a new potential drug target.

Drugs could be developed to keep the types of cancers that likely recur in the bone from returning, Taichman said. For example, these drugs could either halt or disrupt how the cancer cells enter or behave in the niche, or keep the cancer cells from out-competing the stem cells.

Cancer cells act a lot like stem cells in that they must reproduce, so the U-M research group hypothesized that prostate cancer cells might travel to the niche during metastasis. One of the jobs of the niche is to keep hematopoietic stem cells from proliferating -- which may be the case for cancer cells, as well, the researchers found.

So why does cancer recur? Say a person has a tumor and surgeons cut it out or do radiation, but it recurs in the bone marrow five years later, Taichman said. Those cancer cells had been circulating in the body well before the tumor was discovered, and one place those cancer cells hid is the niche.

"So what have the cancer cells been doing during those five years? Now we have a partial answer -- they've been sitting in this place whose job it is to keep things from proliferating and growing," Taichman said.

"Our work also provides an explanation as to why current chemotherapies often fail in that once cancer cells enter the niche, most likely they stop proliferating," said Yusuke Shiozawa, lead author of the study. "The problem is that most of the drugs we use to try to treat cancer only work on cells that are proliferating."

Metastases are the most common malignant tumors involving the skeleton, and nearly 70 percent of patients with breast and prostate cancer have bone involvements. Roughly 15 percent to 30 percent of patients with lung, colon, stomach, bladder, uterus, rectum, thyroid or kidney cancer have bone lesions.

Researchers aren't quite sure how the cancer cells out-compete the stem cells in the niche. However, they do know the stem cells were displaced because when cancer cells were in the niche scientists also found evidence of immature blood stem cells in the blood stream, instead of in the marrow where they were supposed to be, Taichman said.

"Eventually the entire blood system is going to collapse," he said. "For example, the patient ultimately becomes anemic, gets infections, and has bleeding problems. We really don't know why people with prostate cancer die. They end up dying from different kinds of complications in part because the marrow is taken over by cancer."

The next step is to find out how the tumor cell gets into the niche and becomes dormant, and exactly what they do to the stem cells when they are there. Researchers also want to know if other types of cancer cells, such as breast cancer, also go to the niche.

The study appears online in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Co-authors are: Elizabeth Pedersen, Aaron Havens, Younghun Jung, Anjali Mishra, Jeena Joseph, Jin Koo Kim, Anne Ziegler, Michael Pienta, Jingcheng Wang, Junhui Song and Paul Krebsbach of the U-M School of Dentistry; Lalit Patel, Chi Ying, Robert Loberg and Kenneth Pienta of the departments of Urology and Internal Medicine at the U-M Medical School.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:21

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Marcadores:

Câncer próstata

Scientists Find a Key to Maintaining Our DNA: Provides New Clues in Quest to Slow Aging

ScienceDaily (Mar. 24, 2011) — DNA contains all of the genetic instructions that make us who we are, and maintaining the integrity of our DNA over the course of a lifetime is a critical, yet complex part of the aging process. In an important, albeit early step forward, scientists have discovered how DNA maintenance is regulated, opening the door to interventions that may enhance the body's natural preservation of genetic information.

|

Humans have two routes for DNA replication and repair -- a standard route that processes DNA quickly but less accurately, and a high-accuracy route that processes DNA slowly but more accurately. |

The new findings may help researchers delay the onset of aging and aging-related diseases by curbing the loss or damage of our genetic makeup, which makes us more susceptible to cancers and neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's. Keeping our DNA intact longer into our later years could help eliminate the sickness and suffering that often goes hand-in-hand with old age.

"Our research is in the very early stages, but there is great potential here, with the capacity to change the human experience," said Robert Bambara, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics at the University of Rochester Medical Center and leader of the research. "Just the very notion is inspiring."

In the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Bambara and colleagues report that a process called acetylation regulates the maintenance of our DNA. The team has discovered that acetylation determines the degree of fidelity of both DNA replication and repair.

The finding builds on past research, which established that as humans evolved, we created two routes for DNA replication and repair -- a standard route that eliminates some damage and a moderate amount of errors, and an elite route that eliminates the large majority of damage and errors from our DNA.

Only the small portion of our DNA that directs the creation of all the proteins we are made of -- proteins in blood cells, heart cells, liver cells and so on -- takes the elite route, which uses much more energy and so "costs" the body more. The remaining majority of our DNA, which is not responsible for creating proteins, takes the standard route, which requires fewer resources.

But, scientists have never understood what controls which pathway a given piece of DNA would go down. Study authors found, that like a policeman directing traffic at a busy intersection, acetylation directs which proteins take which route, favoring the protection of DNA that creates proteins by shuttling them down the elite, more accurate course.

"If we found a way to improve the protection of DNA that guides protein production, basically boosting what our body already does to eliminate errors, it could help us live longer," said Lata Balakrishnan, Ph.D., postdoctoral research associate at the Medical Center, who helped lead the work. "A medication that would cause a small alteration in this acetylation-based regulatory mechanism might change the average onset of cancers or neurological diseases to well beyond the current human lifespan."

"Clearly, a simple preventative approach would be a key, not to immortality, but to longer, disease-free lives," added Bambara.

DNA replication is an intricate, error-prone process, which takes place when our cells divide and our DNA is duplicated. Duplicate copies of DNA are first made in separate pieces, that later must be joined to create a new, full strand of DNA. The first half of each separate DNA segment usually contains the most errors, while mistakes are less likely to appear in the latter half.

For DNA that travels down the standard route, the first 20 percent of each separate DNA segment is tagged, cut off and removed. This empty space is then backfilled with the latter part -- which is the more accurate section -- of the adjoining piece of DNA as the two segments come together to form a full strand.

In contrast, DNA that travels down the elite route gets special treatment: the first 30 to 40 percent of each separate DNA segment is tagged, removed and backfilled, meaning more mistakes and errors are eliminated before the segments are joined. The end result is a more accurate copy of DNA.

The same situation occurs with the DNA repair process, as the body works to remove damaged pieces of DNA.

Unlike the current work, the majority of aging-related research zeroes in on specific agents that damage our DNA, called reactive oxygen species, and how to reduce them. The new research represents a small piece of the pie, but has the potential to be a very important one.

Bambara's team is investigating the newly identified acetylation regulatory process further to figure out how they might be able to intervene to augment the body's natural safeguarding of important genetic information. They are studying human and yeast cell systems to determine how proteins in cells work together to trigger acetylation, which adds a specific chemical to the proteins involved in DNA replication and repair. Researchers are manipulating cells in various ways, through damage or genetic alterations, to see if these changes activate or influence acetylation in any way.

Though they are far from identifying compounds or existing drugs to test, they do see this research having an impact in the future.

"The translational rate is becoming better and better. Today, the course between initial discovery and drug development is intrinsically faster. I could see having some sort of therapeutic that helps us live longer and healthier lives in 25 years," said Bambara.

The work was funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences at the National Institutes of Health. In addition to the researchers at Rochester, Ulrich Hübscher, D.V.M., from the University of Zurich and Judith Campbell, Ph.D., from the California Institute of Technology contributed to the research.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:19

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Marcadores:

DNA

Plant Oil May Hold Key to Reducing Obesity-Related Medical Issues, Researcher Finds

ScienceDaily (Mar. 24, 2011) — Scientists have known for years that belly fat leads to serious medical problems, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and stroke. Now, a University of Missouri researcher has found a plant oil that may be able to reduce belly fat in humans.

In his latest study, James Perfield, assistant professor of food science in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources (CAFNR), found that a specific plant oil, known as sterculic oil, may be a key in the fight against obesity. Sterculic oil is extracted from seeds of the Sterculia foetida tree. The oil contains unique fatty acids known to suppress a bodily enzyme associated with insulin resistance, which could indirectly help with reducing belly fat. Previous studies show that reducing the enzyme in rodents improves their metabolic profile, improving insulin sensitivity and reducing chances for later chronic diseases.

"This research paves the way for potential use in humans," Perfield said. "Reducing belly fat is a key to reducing the incidence of serious disease, and this oil could have a future as a nutritional supplement."

To study the compound, Perfield added sterculic oil to the feed of rats that are genetically disposed to have a high amount of abdominal fat. He tested the rats over the course of 13 weeks and found that rats given a diet supplemented with sterulic oil had less abdominal fat and a decreased likelihood of developing diabetes. Perfield gave the rats a relatively small dose of oil each day, comparable to giving three grams to a 250-pound human.

Belly fat, clinically known as intra-abdominal fat, is between internal organs and the torso. Intra-abdominal fat is composed of "adipose" deposits. Unusually high adipose levels trigger health problems that may induce insulin resistance, which causes the body to have difficulty maintaining blood sugar levels. Initially, the body is able to compensate by producing more insulin, but eventually the pancreas is unable to produce enough insulin, thus increasing excess sugar in the bloodstream and setting the stage for diabetes, cardiovascular disease and other obesity-associated health disorders.

Perfield plans to conduct further studies of sterulic oil in hopes of developing a natural nutritional supplement. He says future research will focus on the effectiveness of the oil in humans, as well as any side effects.

"The oil from this seed is very similar to other vegetable oils," Perfield said. "It shares many of the same chemical properties, which could allow it to be easily substituted with other oils. While eating the seed directly may be possible, it's easier to control the amount of oil if you extract it directly."

Perfield presented the research at the Diabetes, Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Dysfunction Symposium in Keystone, Colo. The research was funded by the Diabetes Action Research and Education Foundation, MU Food for the 21st Century, and CAFNR.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:17

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Marcadores:

Obesidade

'Knowing It in Your Gut': Cross-Talk Between Human Gut Bacteria and Brain

ScienceDaily (Mar. 24, 2011) — A lot of chatter goes on inside each one of us and not all of it happens between our ears. Researchers at McMaster University discovered that the "cross-talk" between bacteria in our gut and our brain plays an important role in the development of psychiatric illness, intestinal diseases and probably other health problems as well including obesity.

|

Gut bacteria influence anxiety-like behavior through alterations in the way the brain is wired, new research suggests. |

"The wave of the future is full of opportunity as we think about how microbiota or bacteria influence the brain and how the bi-directional communication of the body and the brain influence metabolic disorders, such as obesity and diabetes," says Jane Foster, associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences of the Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine.

Using germ-free mice, Foster's research shows gut bacteria influences how the brain is wired for learning and memory. The research paper has been published in the March issue of the science journalNeurogastroenterology and Motility.

The study's results show that genes linked to learning and memory are altered in germ-free mice and, in particular, they are altered in one of the key brain regions for learning and memory -- the hippocampus.

"The take-home message is that gut bacteria influences anxiety-like behavior through alterations in the way the brain is wired," said Foster.

Foster's laboratory is located in the Brain-Body Institute, a joint research initiative of McMaster University and St. Joseph's Healthcare in Hamilton. The institute was created to advance understanding of the relationship between the brain, nervous system and bodily disorders.

"We have a hypothesis in my lab that the state of your immune system and your gut bacteria -- which are in constant communication -- influences your personality," Foster said.

She said psychiatrists, in particular, are interested in her research because of the problems of side effects with current drug therapy.

"The idea behind this research is to see if it's possible to develop new therapies which could target the body, free of complications related to getting into the brain," Foster said. "We need novel targets that take a different approach than what is currently on the market for psychiatric illness. Those targets could be the immune system, your gut function…we could even use the body to screen patients to say what drugs might work better in their brain."

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:15

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Marcadores:

Bactérias

Molecular Muscle: Small Parts of a Big Protein Play Key Roles in Building Tissues

ScienceDaily (Mar. 24, 2011) — We all know the adage: A little bit of a good thing can go a long way. Now researchers in London are reporting that might also be true for a large protein associated with wound healing.

The team at the Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology at Imperial College reports in the Journal of Biological Chemistry that a protein generated when the body is under stress, such as in cases of physical trauma or disease, can affect how the protective housing that surrounds each cell develops. What's more, they say, tiny pieces of that protein may one day prove useful in preventing the spread of tumors or fibrosis.

At just 174 nanometers in diameter, tenascin-C is pretty big in the world of proteins, and it looks a lot like a spider with six legs, which are about 10 times longer than its body. Thanks to those long legs, tenascin-C can do real heavy lifting when it comes to wound healing.

"Tenascin-C plays many roles in the response to tissue injury, including, first of all, initiating an immune response and, later, ensuring proper tissue rebuilding," explains Kim Midwood, who oversaw the project.

When the injury alarm is rung, tenascin-C shows up on the scene and attaches to another protein, fibronectin. Together, tenascin-C and fibronectin help to construct the housing, or extracellular matrix, that surrounds each cell.

"The extracellular matrix is the home in which the cells of your body reside: It provides shelter and nutrients and also sends signals to the cell to tell it how to behave," says Midwood. "To make a finished tissue, the matrix must be carefully built."

Tenascin-C's job is a temporary one. When your hand is cut, for example, it appears at the edges of the wound and then goes away when scar tissue develops, says postdoctoral research associate Wing To: "Tenascin-C is thought to play a major role during the rebuilding phase of tissue injury by promoting regeneration of tissue that has been damaged."

If the extracellular matrix were a construction site, tenascin-C could be seen as the scaffold upon which the weaving of fibronectin threads, or fibrils, is done. "Tenascin-C has multiple arms, and we have shown that it has multiple binding sites for fibronectin," Midwood says. "In this way, it can bind to many fibronectin fibrils at once and help to form the whole tissue by linking the fibrils together. Then, when the repair is done, the scaffolding is taken down."

Midwood and To systematically determined where tenascin-C and fibronectin bind together. They also identified small parts of tenascin-C, known as domains, that can bind to only one fibronectin fibril apiece.

"The small domains act as caps of the scaffold. No more fibronectin fibrils can bind once these caps are in place," Midwood says. So, in essence, they found that certain pieces of tenascin-C determine when fibril building should stop once enough, but not too much, tissue is made.

The findings could be especially useful for creating therapies for conditions in which there is aberrant extracellular matrix deposition, such as in cancers, fibrotic conditions or chronic non-healing wounds, adds To.

In abnormal conditions, such as in the case of a tumor cell, "the home that's made of fibronectin helps it to survive, shelters it and provides signals that enable it to proliferate," says Midwood. "As the tumor thrives, the home keeps on growing, expanding to destroy the existing neighborhood."

Similarly, in fibrotic diseases, tissue rebuilding rages out of control -- with too much fibronectin assembly -- so that it takes over the whole affected organ, Midwood says.

"In the end, we found that tenascin-C has both stop and go functions cleverly concealed in the same molecule," Midwood says. "The large spiderlike protein may provide a scaffold for building, and the small domains of the protein block excess building. Small domains may be therapeutically useful in situations where too much fibronectin drives disease."

If certain domains can stop uncontrolled matrix deposition in conditions where there is an increase in unwanted extracellular matrix, such as in fibrosis, then they could be useful tools for controlling such diseases.

Meanwhile, To says, in conditions with high levels of tenascin-C degradation by enzymes, for example in nonhealing chronic wounds, that may expose active tenascin-C domains, "if we can stop the production of these domains during disease progression with specific inhibitors, maybe we could help ameliorate the condition.

Similarly we could try and get the cells to make tenascin-C variants that are not as easily broken down by enzymes to help facilitate wound healing."

Midwood and To's paper was named a "Paper of the Week" by the Journal of Biological Chemistry's editorial board, landing it in the top 1 percent of all papers published over the year in the journal. The project was funded by the charity Arthritis Research UK and by the Kennedy Institute Trustees, and the paper will appear in a forthcoming print issue of the journal.

Postado por

SHDA_CECAL FIOCRUZ

às

07:13

0

comentários

Enviar por e-mailPostar no blog!Compartilhar no XCompartilhar no FacebookCompartilhar com o Pinterest

Marcadores:

Músculos

Assinar:

Comentários (Atom)