| |

|

Pesquisadores da Comissariado francês de Energia Atômica (CEA) e da Universidade Joseph Fourier demonstraram que as nanopartículas de dióxido de titânio afetam uma barreira fisiológica essencial para proteger o cérebro: a barreira hematoencefálica.

As nanopartículas de titânio - também conhecidas como nano-TiO2 - são produzidas em escala industrial e são encontrados em cosméticos, incluindo os protetores solares, em tintas e também em revestimentos autolimpantes e superfícies bactericidas.

O estudo demonstrou que as nanopartículas rompem a barreira, gerando inflamação e uma diminuição da atividade da glicoproteína-P, uma proteína essencial para a eliminação de substâncias tóxicas nos órgãos vitais como o cérebro.

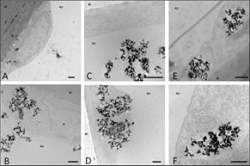

Modelo da barreira hematoencefálica

Estudos anteriores demonstraram que as nanopartículas podem danificar o DNA das células. Outros pesquisadores chegam a comparar as nanopartículas ao amianto. Mas pouco se sabia até agora sobre seus efeitos sobre o sistema nervoso central.

Um estudo feito em ratos havia mostrado que, após uma instilação nasal, o nano-TiO2 pode chegar ao cérebro, principalmente no hipocampo e bulbo olfatório.

Os pesquisadores então se perguntaram como essas nanopartículas podem ser encontradas no cérebro, normalmente protegido de elementos tóxicos por uma estrutura especial: a barreira hematoencefálica.

Para responder a esta pergunta, a equipe usou um modelo in vitro de células desenvolvido para reproduzir a barreira de proteção do cérebro.

Graças ao modelo celular, que também é utilizado pela indústria farmacêutica para testar os candidatos a medicamentos em estudos pré-clínicos, os pesquisadores demonstraram que a exposição in vitro às nanopartículas de TiO2 resulta na acumulação cerebral do material nanotecnológico.

Perturbação da função cerebral

O modelo desenvolvido pelos pesquisadores reconstrói a barreira combinando dois tipos celulares principais: as células endoteliais (do sistema circulatório), cultivadas em uma membrana semi-permeável, e células gliais (do sistema nervoso). O modelo apresenta as principais características da barreira hematoencefálica real, incluindo a humana.

Os pesquisadores demonstraram que a exposição aguda e/ou crônica ao nano-TiO2 leva a um acúmulo dessas nanopartículas nas células endoteliais.

Elas também alteram a função protetora, primeiro, quebrando a barreira e, segundo, diminuindo a atividade da P-glicoproteína, uma proteína encontrada nas células endoteliais, cujo papel é bloquear as toxinas que podem adentrar ao sistema nervoso central.

Os resultados sugerem que a presença de nano-TiO2 poderia ser a causa da inflamação vascular cerebral. Eles também sugerem que a exposição crônica, in vivo, a essas nanopartículas pode levar à sua acumulação no cérebro, com um risco de perturbação da função cerebral.