|

| Vários sensores de açúcar do intestino e do pâncreas também estão presentes exatamente nas mesmas células sensíveis ao sabor doce que já se conhecia. |

Detectores gustativos

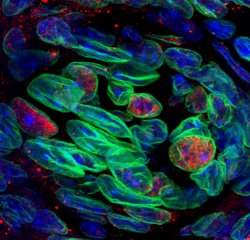

Um novo estudo aumenta dramaticamente o conhecimento que os cientistas tinham até hoje sobre como as células do paladar detectam açúcares.

Este está sendo considerado um passo-chave no desenvolvimento de estratégias para limitar o consumo excessivo dessas substâncias, um elemento essencial nas dietas, no tratamento da obesidade e no controle alimentar de pessoas com diabetes.

Os cientistas do Centro Monell, nos Estados Unidos, descobriram que as células gustativas têm vários detectores adicionais de açúcar, além do receptor de doce anteriormente conhecido.

"Detectar a doçura de açúcares nutritivos é uma das tarefas mais importantes de nossas células gustativas," explica o Dr. Robert Margolskee, coordenador da pesquisa. "Muitos de nós comem muito açúcar e para ajudar a limitar o consumo excessivo precisamos entender melhor como uma célula gustativa 'sabe' que algo é doce."

Sensores do sabor doce

Os cientistas já sabiam que o receptor T1r2+T1r3 é o principal mecanismo que permite que as células gustativas detectem muitos compostos doces, incluindo os açúcares como a glicose e a sacarose, assim como os adoçantes artificiais, incluindo a sacarina e o aspartame.

No entanto, alguns aspectos do sabor doce não podem ser explicados por estes receptores.

Por exemplo, embora o receptor contenha duas subunidades, que devem se unir para que ele funcione corretamente, a equipe de Margolskee tinha descoberto anteriormente que ratos geneticamente modificados sem a subunidade T1r3 ainda eram capazes de detectar normalmente a glicose e outros açúcares.

Sabendo também que os sensores de açúcar no intestino são importantes para a detecção e absorção dos açúcares, e que os sensores metabólicos no pâncreas são fundamentais para a regulação dos níveis sanguíneos de glicose, os cientistas decidiram pesquisar se esses mesmos sensores também poderiam ser encontrados nas células gustativas.

A resposta foi positiva, mostrando que vários sensores de açúcar do intestino e do pâncreas também estão presentes exatamente nas mesmas células sensíveis ao sabor doce que têm o receptor T1r2+T1r3.

Mistérios do sabor doce

Os diferentes sensores de sabor doce podem ter papéis variados.

Um sensor de glicose intestinal, que agora foi localizado também nas células sensíveis ao sabor doce na boca, pode fornecer uma explicação para um outro mistério do gosto doce: por que uma pitada de sal adicionada aos alimentos assados realça o gosto doce.

Conhecido como SGLT1, este sensor é um transportador de glicose que leva o açúcar para o detector de sabor doce quando o sódio está presente, desencadeando assim o processo que faz a célula registrar a sensação de doçura.

No pâncreas, o sensor de açúcar conhecido como canal KATP monitora os níveis de glicose e desencadeia a liberação de insulina quando esses níveis se elevam.

Os autores especulam que o KATP possa funcionar nas células detectoras de sabor doce para modular a sensibilidade das células aos açúcares de acordo com as necessidades metabólicas.

Por exemplo, este sensor pode responder aos sinais hormonais do intestino ou do pâncreas para tornar as células menos sensíveis aos doces depois que a pessoa acabou de comer um pedaço de torta açucarada e não precisa de mais energia.

Limitação do consumo de doces

"Esse conhecimento poderá ajudar-nos a compreender como limitar o consumo excessivo de alimentos doces," diz a Dra Karen Yee, que realizou os experimentos.

Os cientistas planejam agora estudar as complexas ligações entre as células do paladar e os sistemas digestivo e endócrino.