Neste Blog realizamos: 1 - Atualização sobre SAÚDE PÚBLICA, PESQUISA BIOMÉDICA E BIOSSEGURANÇA. 2 - Atualização sobre a ocorrência de Doenças de importância em animais de laboratório e outras espécies. 3 - Troca de Informações sobre Doenças Infecciosas, Zoonoses, Licenciamento Ambiental, Defesa Sanitária Animal, Vigilância Sanitária, Boas Práticas de Laboratório e demais assuntos relacionados à sanidade e Saúde Pública.

Pesquisar Neste Blog

quinta-feira, 7 de abril de 2011

Ethology - Volume 117, Issue 5 Page i - 471

Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition - June 2011 Volume 95, Issue 3 Pages 273–408

Jornalismo científico: uma atividade em crise?

Fiocruz inaugura Casa Eficiente no campus de Manguinhos

Estrutura apresenta ao público geral alternativas para economizar água e energia

Cuidar do meio ambiente – condição necessária para garantir a saúde e a qualidade de vida da população – é compromisso da Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz). E este compromisso foi reafirmado hoje, Dia Mundial da Saúde (7/4), quando a Fundação inaugurou a Casa Eficiente, um local destinado à experimentação e à demonstração de alternativas para uso racional de água e energia. A Casa Eficiente da Fiocruz surgiu como uma espécie de laboratório, onde soluções de engenharia e arquitetura pudessem ser testadas em escala piloto para, depois, serem estendidas a toda a Fundação. Esse objetivo, entretanto, foi ampliado e, hoje, a casa é um espaço de educação ambiental, visando divulgar para o público geral alternativas ecologicamente corretas. Desde o lado de fora, os visitantes já podem constatar os diferenciais da casa, toda feita de madeira certificada de reflorestamento. Também é possível observar três caixas d’água: uma convencional, uma ligada a um sistema que coleta água da chuva e outra acoplada a um aquecedor solar feito de garrafa pet.

O aquecedor é um sistema fechado, que funciona como uma estufa de garrafa pet, para não perder energia, e contém embalagens tetrapack pintadas de preto, para absorver ao máximo o calor do sol. Como a água fria é mais pesada e desce e a água quente é mais leve e sobe, o líquido circula pelo aquecedor e vai esquentando. O resultado é percebido no banheiro da casa, onde – ao lado da descarga que usa água da chuva – o chuveiro pode ter água quente sem consumir eletricidade. “Mesmo que o morador queira tomar um banho bem quente, ele economiza energia. Sem o aquecedor solar, ele teria que colocar o chuveiro elétrico no modo “inverno”. Aproveitando a energia solar, ele já alcança a temperatura desejada no modo “verão”, que consome menos energia”, explica o engenheiro Tatsuo Shubo, coordenador da área de infraestrutura e ambiente da Diretoria de Administração do Campus (Dirac/Fiocruz).

Na casa também é possível visualizar as diferenças entre uma torneira convencional, na qual o fluxo de água só é interrompido se alguém fechar, e duas planejadas para desligar automaticamente, sendo uma por sistema mecânico e a outra eletrônica. As duas últimas representam uma enorme economia de água em relação à primeira. A torneira eletrônica, contudo, é ainda mais eficiente. “Ela libera exatamente o mesmo volume de água a cada vez que é acionada, enquanto o sistema mecânico é irregular”, afirma Tatsuo. Além das torneiras, os visitantes podem comparar a eficiência de diferentes aparelhos de ar condicionado. Embora, na aparência, eles sejam semelhantes, o modelo de classe A consome menos energia para resfriar o ambiente, se comparado ao modelo de classe C.

As lâmpadas – várias delas instaladas num painel – também reservam surpresas. As mais finas são as que mais iluminam e com um gasto inferior de energia. “A Fiocruz firmou uma parceria com a Light para substituir todas as lâmpadas da Fundação pelas mais eficientes, o que vai gerar uma economia de R$ 3 milhões por ano”, calcula o engenheiro. Experimentando, na prática, os visitantes constatam que, além da lâmpada, o tipo de luminária e a cor das paredes também determinam a eficiência da iluminação. Outra curiosidade encontrada na casa é a lâmpada RGB, que, por controle remoto, varia gradualmente sua temperatura de cor ou, em outras palavras, simula com perfeição a mudança do dia para a noite. Por isso, ela é uma ferramenta útil em pesquisas que requerem o desenvolvimento de animais e plantas em laboratório.

Cientistas brasileiros criam nervo artificial

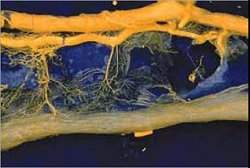

Fatty Liver: How a Serious Problem Arises

|

3D-illustration of a human liver with blood vessels (red and blue) and bile duct (green). |

Simple Chemical Cocktail Shows First Promise for Limb Re-Growth in Mammals

|

Newt. Just as injured newts can sprout new limbs, a simple chemical cocktail shows promise for limb re-growth in mammals. It nudges mouse cells on a path toward regeneration. |

Structure Formed by Strep Protein Can Trigger Toxic Shock

|

M1 joints (red) and fibrinogen struts (green) form a scaffold. Dense assemblies trigger a pathological response that can lead to toxic shock. |

Chemical Engineers Have Designed Molecular Probe to Study Disease

|

This shows enhanced detection of endogenous protease activity. |

Scientists Develop New Technology for Stroke Rehabilitation

|

The new technologies will help patient rehabilitation. |