|

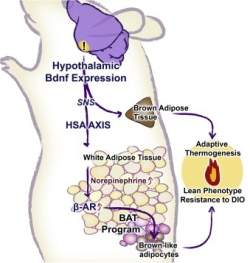

| O caminho bioquímico para geração da gordura boa começa no hipotálamo e termina nas células adiposas brancas |

Gordura branca e marrom

Cientistas da Universidade de Ohio (EUA) identificaram um mecanismo biológico que transforma gordura branca em marrom.

O homem tem dois tipos de tecido adiposo: o marrom, ligado à regulação da temperatura e abundante em recém-nascidos; e o branco, cuja função é acumular energia no corpo e está mais presente em adultos.

A gordura branca está associada à obesidade e à falta de exercícios. É a gordura indesejada e que muitos querem se livrar do excesso.

A novidade, publicada na edição de setembro da revista Cell Metabolism, poderá auxiliar no desenvolvimento de novas estratégias para tratar a obesidade.

Gordura boa

O processo de formação da gordura boa só foi desvendado em 2008.

Em 2009, outro grupo descobriu como modificar células para que estas produzam a gordura boa.

O novo estudo, feito em modelo animal, demonstrou que a transformação da gordura ruim em boa é possível devido à ativação de uma enervação e de um caminho bioquímico que começa no hipotálamo (área cerebral envolvida no balanço energético) e que termina nas células adiposas brancas.

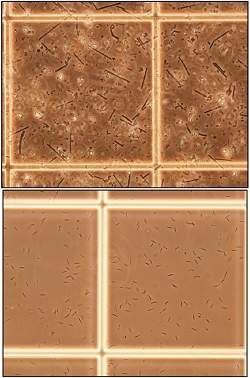

A transformação das gorduras foi observada quando os animais foram colocados em um ambiente mais rico, com maior variedade de características e desafios físicos e sociais.

Ambiente estimulante

Os camundongos foram colocados em recipientes contendo rodas de girar, túneis, cabanas, brinquedos e diversos outros elementos, somados a alimento e água em quantidades abundantes.

Um grupo controle também foi exposto a água e alimento sem limites, mas em ambiente sem dispositivos para que pudessem se exercitar.

Segundo os cientistas, a maior transformação de gordura branca e marrom foi associada a um ambiente fisicamente estimulante, mais do que à quantidade de alimentos ingerida.

"Os resultados do estudo sugerem o potencial de induzir a transformação de gordura branca em gordura marrom por meio da modificação do nosso estilo de vida ou pela ativação farmacológica desse caminho bioquímico", disse Matthew During, professor de neurociência e um dos autores do estudo.