Clonagem Humana

Cientistas afirmam ter criado células-tronco humanas por meio de clonagem.

Essencialmente, a técnica envolve pegar um óvulo humano e combiná-lo com uma célula de outra pessoa adulta, sem retirar o DNA original da célula.

Esta área de pesquisas é altamente controversa, não apenas por suas implicações éticas, mas também por causa de uma fraude científica recente.

Em 2004, o cientista sul-coreano Hwang Woo-suk ganhou fama meteórica ao anunciar que teria produzido uma linhagem de células-tronco geradas a partir do embrião de um clone humano.

Como todo bom meteoro, Hwang queimou-se na atmosfera quando se descobriu que ele tinha forjado resultados, além de ter obtido os óvulos de forma antiética e ilegal.

Preservando o DNA

Agora, Scott Noggle, Dieter Egli e seus colegas do Laboratório da Fundação de Células-Tronco de Nova Iorque (EUA), anunciaram, em um artigo publicado na revista Nature, ter alcançado resultados intermediários, mas por uma via diferente.

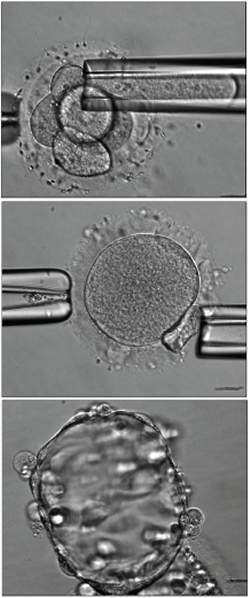

Eles usaram uma tecnologia de clonagem chamada transferência de núcleos de célula somática.

A técnica mais comum de clonagem consiste na remoção do núcleo de um óvulo e sua substituição pelo núcleo da célula do doador, cujo DNA é então inserido no óvulo inicial. Imerso em nutrientes, o óvulo se divide, passando então por uma reprogramação genética, assumindo o DNA do doador.

Na nova técnica, o DNA do óvulo é mantido, recebendo o material genético de células epiteliais de um doador adulto.

|

| "Pode ser um bom momento para as Nações Unidas começarem a forjar regulamentações ou restrições sobre a clonagem, que têm estado paralisadas pelo debate político e religioso," afirma a revista Nature em editorial. "[E] pacientes desesperados vão encontrar médicos prontos a lhes dar tratamentos com células-tronco embrionárias não-comprovados e inseguros."[Imagem: Noggle et al./Nature] |

O resultado é uma célula triploide, com três pares de cromossomos: 23 do óvulo original e 46 (dois pares de 23) da célula do doador - teoricamente um embrião inviável, embora ele não tenha sido deixado para se desenvolver.

O óvulo se desenvolveu até o estágio conhecido como blastocisto, composto por cerca de 100 células.

O blastocisto é usado como fonte de células-tronco embrionárias, usadas em inúmeras pesquisas e vistas como um recurso futuro para a cura de várias doenças.

Os cientistas afirmam ter visto nas células do embrião triploide indícios de células-tronco embrionárias normais, o que comprovaria a importância de se manter o DNA original do óvulo.

Isto também pode ser uma demonstração de que as chamadas "técnicas tradicionais" de clonagem não são eficientes como se acreditava.

Células-tronco personalizadas

A clonagem é um recurso idealizado para evitar o problema da rejeição que ocorre quando um paciente recebe células-tronco de um doador.

Neste caso, o sistema imunológico do receptor vê as células-tronco como invasoras, exigindo o uso de imunossupressores, o que complica e pode até inviabilizar o tratamento.

Com a clonagem, torna-se teoricamente possível criar "células-tronco personalizadas", criadas com o próprio DNA do receptor, evitando então o problema da rejeição.

Ética na clonagem

A pesquisa está em um passo bastante inicial. Um editorial da revista Nature, onde a pesquisa foi publicada, afirma que os embriões triploides são geneticamente anômalos e inviáveis.

Os pesquisadores vão precisar ainda produzir um embrião diploide, com 46 cromossomos, antes de pensar em usar terapeuticamente as células-tronco clonadas.

Se eles conseguirem, recomeçará então todo o debate ético sobre o que fazer com estes embriões, até que ponto eles poderão ser deixados crescer, e se será permitida a realização da clonagem reprodutiva.

"Pode ser um bom momento para as Nações Unidas começarem a forjar regulamentações ou restrições sobre a clonagem, que têm estado paralisadas pelo debate político e religioso," afirma a revista Nature em editorial. "[E] pacientes desesperados vão encontrar médicos prontos a lhes dar tratamentos com células-tronco embrionárias não-comprovados e inseguros."